Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: January 8, 2024. Catching up. Last week we simply wished you a happy New Year, so this week we’ll try to make up for it and cover the first two weeks of the year. January 5th should be officially named Piano Day, as on this day three great pianists were born: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, in 1920, Alfred Brendel, in 1930, and Maurizio Pollini, in 1942. Pollini still performs, but we stopped attending his concerts some years ago: he’s now just a shadow of his great self. This doesn’t diminish his prodigious talent that he brilliantly displayed for decades with virtuosity and incisive repertoire, which, unique to a pianist of his stature, included the music of many modern composers. (In comparison, the repertoire of his compatriot, the perfectionist Michelangeli, was very narrow).

displayed for decades with virtuosity and incisive repertoire, which, unique to a pianist of his stature, included the music of many modern composers. (In comparison, the repertoire of his compatriot, the perfectionist Michelangeli, was very narrow).

Two prominent Soviet cellists were born during these two weeks, Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, on January 6th of 1908, and Daniil Shafran, on January 13th of 1923. Knushevitsky is not well known outside of Russia but in his day, he was considered one of the very best (in the rank-obsessed Soviet Union, he was the third best cellist, after Rostropovich and Shafran; had he not drunk, he might have been number one). In 1940, Knushevitsky, David Oistrakh and Lev Oborin organized a very successful trio; they performed worldwide to great acclaim. Knushevitsky and Oistrakh also played together in one of the incarnations of the Beethoven quartet. Knushevitsky died at the age of 55 from a heart attack, alcoholism probably contributing to his early death. Here’s the famous second movement from Schubert’s Piano Trio no. 2, which Stanley Kubrick used so effectively in his Barry Lindon. It’s performed by David Oistrakh, violin, Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, cello, and Lev Oborin, piano. The recording was made in 1947. You can also find the complete Triohere. And here, from 1950, is Sviatoslav Knushevitsky’s recording of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. Alexander Gauk leads the Great Radio Orchestra. As for Shafran, you can read more about him in one of our earlier entries.

Another Russia-born string player has an anniversary this week: Nathan Milstein, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. Odessa, where Milstein was born on January 13th of 1904, was back then part of the Russian empire. Now, spelled Odesa, it is in free Ukraine, being bombed by Russia almost daily. Speaking of Russia, Aleksander Scriabin was born on January 6th of 1872 in Moscow. His early piano pieces were charming imitations of Chopin’s but later he developed a musical language all his own, with a very fluid tonality, if not quite atonal. His grandiosity, both personal and musical, and his attempts to synthesize music and color didn’t age well (especially in his orchestral output), but his piano music is still played very often and is of the highest quality.

Among other anniversaries: Francis Poulenc’s 125th was celebrated on January 7th (he was born in 1899). Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, who died tragically young, aged 26, from tuberculosis, but left us a tremendous Stabat Mater and a brilliant intermezzo La serva padrona (Sonya Yoncheva is great as Serpina in this production), was born in a small town of Jesi, Italy, on January 4th of 1710. Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: January 1, 2024. Happy New Year!

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: December 25, 2023. Christmas. We wish our listeners a Merry Christmas! On this wonderful day, we won’t bother you with disquisitions and analyses but will present some Christmas music for your pleasure – and this joyful piece is perfect for the occasion. It’s the first section of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, a cantata known for the initial words of the first chorus as Jauchzet, frohlocket! (Shout for joy, exult). It was first performed on this day in 1734, in the morning, at St. Nicholas; and then in the afternoon, at St. Thomas in Leipzig: Bach, as Thomaskantor, was the music director of both churches and led both performances. What we will hear is a recording made in January of 1987 by John Eliot Gardiner conducting the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir and several prominent soloists, Anne-Sophie von Otter among them. Enjoy and see you in 2024!Permalink

Christmas! On this wonderful day, we won’t bother you with disquisitions and analyses but will present some Christmas music for your pleasure – and this joyful piece is perfect for the occasion. It’s the first section of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, a cantata known for the initial words of the first chorus as Jauchzet, frohlocket! (Shout for joy, exult). It was first performed on this day in 1734, in the morning, at St. Nicholas; and then in the afternoon, at St. Thomas in Leipzig: Bach, as Thomaskantor, was the music director of both churches and led both performances. What we will hear is a recording made in January of 1987 by John Eliot Gardiner conducting the English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir and several prominent soloists, Anne-Sophie von Otter among them. Enjoy and see you in 2024!Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: December 18, 2023. Three Pianists. During the last month, we were preoccupied with composers and completely ignored the performers, who bring their music to the public. So today we bring you three wonderful pianists: Radu Lupu, a Romanian, Mitsuko Uchida, born in Japan, and András Schiff, a British-Hungarian. All three belong to the same generation: Lupu was born in 1945 (on November 30th), Uchida in 1948 (on December 20th), and Schiff – in 1953, on December 21st. Uchida and Schiff are still performing, Lupu died on April 17th of last year.

to the public. So today we bring you three wonderful pianists: Radu Lupu, a Romanian, Mitsuko Uchida, born in Japan, and András Schiff, a British-Hungarian. All three belong to the same generation: Lupu was born in 1945 (on November 30th), Uchida in 1948 (on December 20th), and Schiff – in 1953, on December 21st. Uchida and Schiff are still performing, Lupu died on April 17th of last year.

Radu Lupu is widely considered one of the greatest pianists of his time. He studied in Moscow with Heinrich Neuhaus, who also taught Richter and Gilels. In the three years from 1966 to 1969, he won three major piano competitions, the Cliburn, the Enescu, and the Leeds, and embarked on an international career with successful concerts in London. Though he played all major composers of the 18th and 19th centuries, he was most closely associated with the music of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. Here is Schubert’s Impromptu in A flat major, D. 935, no. 2 from a legendary 1982 Decca recording of Schubert’s Impromptus D. 899 and D.935.

Lupu probably didn’t need any competition wins for his tremendous talent to be noticed by the public and the critics. Mitsuko Uchida didn’t need them either: all she got from competing in the majors was second place in the 1975 Leeds (a solid Dmitry Alekseyev won, and Schiff shared the third prize). Uchida’s family moved to Vienna when she was 12. She studied there at the Academy of Music (Wilhelm Kempff was one of her teachers). In the 1980s Uchida moved to London and has lived there since. In 2009, she was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, the second-highest British award. Uchida is rightfully famous for her Mozart, but her repertoire is very broad, from Haydn to Schoenberg. Here’s Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 12 in F major, K.332, and here – one of the 12 Etudes by Debussy, no. 3, Pour les Quartes.

András Schiff fared even worse than Uchida in international competitions: in addition to third prize at the Leeds which we mentioned above, all he got was a shared fourth prize at the 1974 Tchaikovsky competition (the 18-year-old Andrei Gavrilov was the winner; a talented pianist, he had an interesting but brief career, which in its significance could not be compared to Schiff’s). András Schiff was born into a Jewish family in Budapest. He studied at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music there (György Kurtág was one of his professors and Zoltán Kocsis, who studied there at the same time, became a friend). He also took summer classes with Tatiana Nikolayeva and Bella Davidovich. Since the late 1980s he, like Uchida, has been living in London, and like her, was knighted (in 2014). Schiff is one of the most admired pianists of his generation; he feels comfortable in many venues: he plays recitals and concertos, loves ensemble playing, and often accompanies singers. His Bach is wonderful, but so are his Mozart and Haydn, Schubert and Schumann. He often played the music of his fellow Hungarian Bela Bartók but is very critical of the current political situation in his country of birth and even said that he’ll never set foot there. Here’s András Schiff playing Bach’s French Suite no. 4, recorded in 1991. This recording was made in Reitstadel, a former animal feed storage barn built in the 14th century and in our time converted into a concert hall. It’s located in the Bavarian town of Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz. Permalink

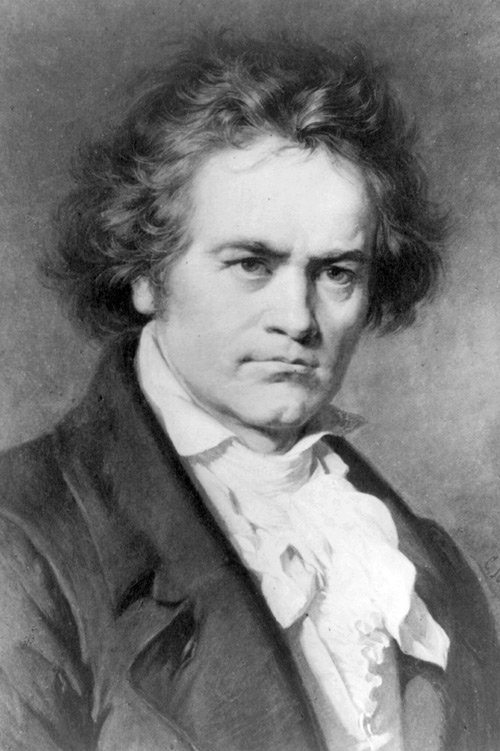

This Week in Classical Music: December 11, 2023. Beethoven and Berlioz. On December 16th we’ll celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven’s 253rd anniversary. As we thought of it, we remembered what happened on this date three years ago when the world was supposed to celebrate a monumental date, Beethoven’s 250th. It didn’t happen, as our musical organizations couldn’t bring themselves to honor a white male composer – that was the year of Critical Race Theory run amok, DEI ruling the world, and sanity running for cover On the website Music Theory’s White Racial Frace, Philip Ewell, a black musicologist, published an article titled “Beethoven Was an Above Average Composer – Let’s Leave It at That” which contained a sentence: “But Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is no more a masterwork than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells.” Alex Ross, our most important public music critic, felt compelled to respond to this nonsense with an article of his own, publishing “Black Scholars Confront White Supremacy in Classical Music” in the New Yorker magazine. The article's subtitle was: “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.” In the New York Times, Anthony Tomassini, the chief classical music critic who is no longer with the newspaper, wrote an article about the harm of the blind, behind-the-curtain orchestral auditions. Those were widely accepted a quarter century ago to avoid any racial or gender biases, but Tomassini argued that it hinders the racial diversification of our orchestras: “The audition process should take into account race, gender and other factors.” We wonder if he still thinks that way, or was that just intellectual cowardice, an attempt to cover his hide: after all, for decades he was toiling in a field that purportedly turned out to be racist through and through, and in all these years it never occurred to him to assess it in racial terms. All of this was just three years ago. This major burst of insanity seems to be behind us and hopefully will dissipate completely, sooner rather than later. Do we need to add a disclaimer that we are totally against any racial and gender discrimination, whether in music or any other cultural or social sphere? We hope not.

remembered what happened on this date three years ago when the world was supposed to celebrate a monumental date, Beethoven’s 250th. It didn’t happen, as our musical organizations couldn’t bring themselves to honor a white male composer – that was the year of Critical Race Theory run amok, DEI ruling the world, and sanity running for cover On the website Music Theory’s White Racial Frace, Philip Ewell, a black musicologist, published an article titled “Beethoven Was an Above Average Composer – Let’s Leave It at That” which contained a sentence: “But Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is no more a masterwork than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells.” Alex Ross, our most important public music critic, felt compelled to respond to this nonsense with an article of his own, publishing “Black Scholars Confront White Supremacy in Classical Music” in the New Yorker magazine. The article's subtitle was: “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.” In the New York Times, Anthony Tomassini, the chief classical music critic who is no longer with the newspaper, wrote an article about the harm of the blind, behind-the-curtain orchestral auditions. Those were widely accepted a quarter century ago to avoid any racial or gender biases, but Tomassini argued that it hinders the racial diversification of our orchestras: “The audition process should take into account race, gender and other factors.” We wonder if he still thinks that way, or was that just intellectual cowardice, an attempt to cover his hide: after all, for decades he was toiling in a field that purportedly turned out to be racist through and through, and in all these years it never occurred to him to assess it in racial terms. All of this was just three years ago. This major burst of insanity seems to be behind us and hopefully will dissipate completely, sooner rather than later. Do we need to add a disclaimer that we are totally against any racial and gender discrimination, whether in music or any other cultural or social sphere? We hope not.

Back to Beethoven. We looked up our library, and it turns out that while we have most of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, we don’t have the sonata no. 19, a short and misnumbered piece, easy enough to be well known to practically all young pianists. Beethoven composed it sometime in 1797, about the same time as his sonatas nos. 3 and 4, but it wasn’t published till 1805 and thus acquired its late opus and number. Here it is, performed by Alfred Brendel in a 1992 recording.

sometime in 1797, about the same time as his sonatas nos. 3 and 4, but it wasn’t published till 1805 and thus acquired its late opus and number. Here it is, performed by Alfred Brendel in a 1992 recording.

Also, on this day 220 years ago Hector Berlioz was born in La Côte-Saint-André, a small town halfway between Lyon and Grenoble. Berlioz was one of the greatest composers France ever produced, and a very unusual one at that: he didn’t follow any established schools and didn’t leave any behind. We’ve written about Berlioz many times, and he requires a separate entry, so for now, here is his symphony cum viola concerto Harold in Italy (parts 1, Harold in the mountains,2, March of the pilgrims, 3, Serenade of an Abruzzo mountaineer, and 4, Orgy of bandits). The great violinist Yehudi Menuhin is playing the viola, with Sir Colin Davis conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra. Permalink

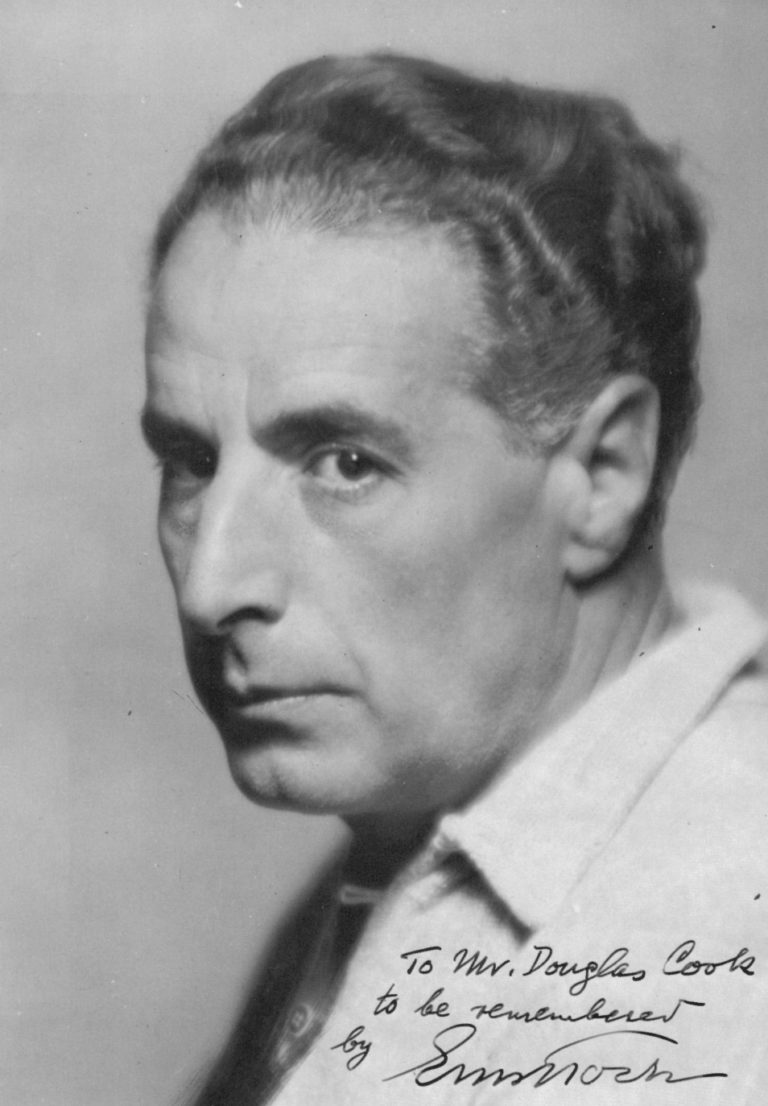

This Week in Classical Music: December 4, 2023. Ernst Toch and more. Erns Toch, the Jewish-Austrian composer, was born on December 7th of 1887 in Leopoldstadt, a poor, mostly Jewish area in Vienna. Toch was one of a group of Austrian and German composers whose lives were upended by the rise of Nazism (Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Karl Weigl, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Berthold Goldschmidt, all Jewish, mostly forgotten except of course for Schoenberg, all talented if to a different degree, had their lives broken in 1933). One thing we find interesting is the ease with which they moved from Austria to Germany. These were two very different empires, one, declining, ruled by the peace-seeking Emperor Franz Joseph from Vienna, another – very much on the ascent, economically, politically and militarily, ruled by the arrogant and insecure Keiser Wilhelm II. But musicians thought nothing of moving from one country to another, from Vienna to Berlin and back, conducting in Hamburg or Leipzig one year and then returning to Austria, teaching at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik and then at Universität für Musik in Vienna. And they didn’t need permission to work as long as positions were available. Musically, the pre-WWI Austria and Germany were one space, even more so than they are now.

Jewish area in Vienna. Toch was one of a group of Austrian and German composers whose lives were upended by the rise of Nazism (Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schreker, Karl Weigl, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Berthold Goldschmidt, all Jewish, mostly forgotten except of course for Schoenberg, all talented if to a different degree, had their lives broken in 1933). One thing we find interesting is the ease with which they moved from Austria to Germany. These were two very different empires, one, declining, ruled by the peace-seeking Emperor Franz Joseph from Vienna, another – very much on the ascent, economically, politically and militarily, ruled by the arrogant and insecure Keiser Wilhelm II. But musicians thought nothing of moving from one country to another, from Vienna to Berlin and back, conducting in Hamburg or Leipzig one year and then returning to Austria, teaching at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik and then at Universität für Musik in Vienna. And they didn’t need permission to work as long as positions were available. Musically, the pre-WWI Austria and Germany were one space, even more so than they are now.

Toch was at his most productive in the 1920s, when he wrote the Concerto for Cello and Chamber Orchestra, Bunte Suite, two short operas, many chamber pieces and piano music. Here’s Bunte Suite, whose sophisticated humor reminds us of the music of another Austrian composer, Ernst Krenek. The Suite is performed by the Karajan Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker, Cornelius Meister conducting. You can read about Toch’s life after Hitler assumed power in last year’s post.

Jean Sibelius was also born this week, on December 8th of 1865. We have to admit that we’re not big fans of the Finnish composer, but his one-movement Symphony no. 7, is a masterpiece. Even though it’s his shortest, about 23 minutes long depending on performance, it took Sibelius 10 years (from 1914 to 1924) to complete. During that time, he managed to complete two more symphonies, nos. 5 and 6. Here’s the Seventh, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Herbert von Karajan.

While Sibelius may not be one of our favorites, Olivier Messiaen, born on December 10th of 1908, clearly is. We’ve written about him on several occasions and will get back to the great French master soon. Also this week: Henryk Górecki, a Polish composer whose minimalist symphonies became very popular with audiences worldwide, born on December 6th of 1933, and César Franck, the composer of one of the best violin sonatas, on December 10th of 1822. Permalink