Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

This Week in Classical Music: November 27, 2023. Maria Callas. We’re a bit early, but next Sunday is the 100th anniversary of Maria Callas, La Divina, as she was known worldwide: she was born on December 2nd of 1923. It feels very strange that’s already been a century since her birth, as her presence is felt as strongly today as on the day she died in 1977: her instantly recognizable voice could be heard on classical music radio stations, on streaming services, on YouTube and (still) on CDs. The means have changed – back then it was LPs that people were buying and listening to – but she’s as adored as ever. Her Casta Diva alone has been heard on YouTube about 35 million times. Callas was so closely associated with Italian opera – Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini – that she seemed Italian, but in fact was American, of Greek descent. She married an Italian, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and, while they were married used his name with her own as Maria Meneghini Callas. She moved to Greece in 1940 and studied voice at the Athen Conservatory. There, she sang in the opera for the first time, appearing as Tosca in 1942. She returned to the US in 1945 but soon left for Italy. Tulio Serafin, the famous conductor who coached generations of singers, became her mentor. In 1947, at the Arena of Verona, he conducted Callas in her first Italian role, as La Gioconda in Ponchielli’s eponymous opera. Her appearance was tremendously successful and brought her career to a different level. During that time she often sang in the rarely produced bel canto operas, mostly because she was the only one who could sing these very difficult roles. She was exceptional as Donizetti’s Anna Boleyn, as Imogene and Norma in Bellini’s Il Pirata and Norma, Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Lady Macbeth and Violetta in Verdi's Macbeth and Traviata, and, of course, as Tosca. For three years she sang in smaller theaters, then, in 1950, she appeared, as Aida in La Scala. Even though her relationship with the management was troubled, in the 1950s La Scala became Callas’s home. Neither did Callas have a rapport with Rudolph Bing, the manager of the Met, where she premiered only in 1956. She had a reputation as a temperamental diva, but many of her colleagues thought that it was her exactness that made her difficult to work with. Later in the 1950s, she started experiencing problems with her voice, which may have contributed to her sometimes-erratic behavior. Some think that it was the loss of weight that affected her voice; in the early 1950s Callas was rather heavy, but then went on a diet and lost about 80 pounds. By the late 1950s, her vibrato was too heavy, sometimes the voice was forced and one could hear pronounced harshness, even though other performances were still excellent. Overall, Callas sang at the top of her form for just 10 years but what glorious years they were! Even her detractors, and there are some, recognize that the interpretations of the roles she sang were incomparable, it’s her voice that some people have problems with. We think that at its peak her voice was uniquely beautiful, and she created exceptional operatic characters that in other interpretations seem dull. Even the often mediocre music (and Italian operas are full of it) sounded exciting when she sang. There are none even close to La Divina on the opera stage today, and we don’t expect to hear anybody of that rank anytime soon.Permalink

was born on December 2nd of 1923. It feels very strange that’s already been a century since her birth, as her presence is felt as strongly today as on the day she died in 1977: her instantly recognizable voice could be heard on classical music radio stations, on streaming services, on YouTube and (still) on CDs. The means have changed – back then it was LPs that people were buying and listening to – but she’s as adored as ever. Her Casta Diva alone has been heard on YouTube about 35 million times. Callas was so closely associated with Italian opera – Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini – that she seemed Italian, but in fact was American, of Greek descent. She married an Italian, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, and, while they were married used his name with her own as Maria Meneghini Callas. She moved to Greece in 1940 and studied voice at the Athen Conservatory. There, she sang in the opera for the first time, appearing as Tosca in 1942. She returned to the US in 1945 but soon left for Italy. Tulio Serafin, the famous conductor who coached generations of singers, became her mentor. In 1947, at the Arena of Verona, he conducted Callas in her first Italian role, as La Gioconda in Ponchielli’s eponymous opera. Her appearance was tremendously successful and brought her career to a different level. During that time she often sang in the rarely produced bel canto operas, mostly because she was the only one who could sing these very difficult roles. She was exceptional as Donizetti’s Anna Boleyn, as Imogene and Norma in Bellini’s Il Pirata and Norma, Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Lady Macbeth and Violetta in Verdi's Macbeth and Traviata, and, of course, as Tosca. For three years she sang in smaller theaters, then, in 1950, she appeared, as Aida in La Scala. Even though her relationship with the management was troubled, in the 1950s La Scala became Callas’s home. Neither did Callas have a rapport with Rudolph Bing, the manager of the Met, where she premiered only in 1956. She had a reputation as a temperamental diva, but many of her colleagues thought that it was her exactness that made her difficult to work with. Later in the 1950s, she started experiencing problems with her voice, which may have contributed to her sometimes-erratic behavior. Some think that it was the loss of weight that affected her voice; in the early 1950s Callas was rather heavy, but then went on a diet and lost about 80 pounds. By the late 1950s, her vibrato was too heavy, sometimes the voice was forced and one could hear pronounced harshness, even though other performances were still excellent. Overall, Callas sang at the top of her form for just 10 years but what glorious years they were! Even her detractors, and there are some, recognize that the interpretations of the roles she sang were incomparable, it’s her voice that some people have problems with. We think that at its peak her voice was uniquely beautiful, and she created exceptional operatic characters that in other interpretations seem dull. Even the often mediocre music (and Italian operas are full of it) sounded exciting when she sang. There are none even close to La Divina on the opera stage today, and we don’t expect to hear anybody of that rank anytime soon.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 20, 2023. The Spaniards and a bit of Genealogy. Three Spanish composers were born this week: Manuel de Falla, on November 23rd of 1876, Francisco Tárrega, on November 21st of 1852, and Joaquin Rodrigo, on November 21st of 1901. Falla is probably the most important of the three – some might say the most important Spanish composer of the 20th century – although Tárrega was also instrumental in advancing Spanish classical music, which prior to the arrival of Tárrega and his friends Albéniz and Granados had been stagnant for many decades, practically since the death of Padre Antonio Soler in 1783. (It’s interesting to note that the Spanish missed out almost completely on symphonic music). Falla’s most interesting works were composed for the stage: the drama La Vida Breve, ballets El Amor Brujo and Three-Cornered Hat, the zarzuela (a Spanish genre that incorporates arias, songs, spoken word, and dance) Los Amores de la Inés. A fine pianist, he also composed many pieces for the piano, Andalusian Fantasy among them. Tárrega’s preferred instrument was the guitar: he was a virtuoso player, and he also composed mostly for the instrument. (Tárrega had a unique guitar with a very big sound, made by one Antonio Torres, a famous luthier). Here’s one of his best-known pieces, Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra), performed by Sharon Isbin.

1901. Falla is probably the most important of the three – some might say the most important Spanish composer of the 20th century – although Tárrega was also instrumental in advancing Spanish classical music, which prior to the arrival of Tárrega and his friends Albéniz and Granados had been stagnant for many decades, practically since the death of Padre Antonio Soler in 1783. (It’s interesting to note that the Spanish missed out almost completely on symphonic music). Falla’s most interesting works were composed for the stage: the drama La Vida Breve, ballets El Amor Brujo and Three-Cornered Hat, the zarzuela (a Spanish genre that incorporates arias, songs, spoken word, and dance) Los Amores de la Inés. A fine pianist, he also composed many pieces for the piano, Andalusian Fantasy among them. Tárrega’s preferred instrument was the guitar: he was a virtuoso player, and he also composed mostly for the instrument. (Tárrega had a unique guitar with a very big sound, made by one Antonio Torres, a famous luthier). Here’s one of his best-known pieces, Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra), performed by Sharon Isbin.

Rodrigo also wrote mostly for the guitar: his most famous piece is Concierto de Aranjuez, from 1939, for the guitar and orchestra. Here’s the concerto’s first movement; John Williams is the soloist; Daniel Barenboim leads the English Chamber Orchestra. The recording is almost fifty years old, from 1974, but still sounds very good.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Sebastian’s eldest son and a wonderful composer in his own right, was born on November 22nd of 1710. Here’s our entry about Wilhelm Friedemann from some years ago. We sympathize with Friedemann: he was brooding, mostly unhappy, and quite unlucky, but he wrote music that we find superior to that of his much more famous brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. And here’s an interesting historical tidbit: one of Wilhelm Friedemann’s harpsichord pupils was young Sara Itzig, daughter of Daniel Itzig, a Jewish banker of Frederick II the Great of Prussia. Daniel, one of the few Jews with full Prussian citizenship, had 13 children; Sara was born in 1761. She was a brilliant keyboardist and commissioned and premiered several pieces by Wilhelm Friedeman and CPE Bach. Sara married Salomon Levy in 1783 and had an important salon in Berlin. One of her sisters, Bella Itzig, married Levin Jakob Salomon; they had a son, Jakob Salomon, who upon converting to Christianity, took the name Bartholdy. His daughter Lea married Abraham Mendelssohn, son of the famous Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Lea and Abraham had two children, Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn; their full name was Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Sara had a big influence on the musical education of her grandnephew Felix. Bella gave a manuscript of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew Passion to her grandson in 1824; Felix conducted the first 19th-century revival of the Passion in 1829. So, there’s a line, quite convoluted but fascinating, going from the Bach family to Felix (and Fanny) Mendelssohn. The Itzigs were a remarkable family: in addition to all the connections above, two other sisters, Fanny and Cecilie Itzig, were patrons of Mozart. Maybe we’ll get to that someday.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 13, 2023. Transitioning. Not in the sense of Classical Connect’s gender identity, but as a state of mind, which being in Rome largely is. CC is back in the US, but already missing Rome.

Papa Mozart (Leopold) was born this week, in 1719. He was a minor composer and music teacher but is remembered as the father of his genius son, whose career he managed (or exploited, as some would say) for many years.

as some would say) for many years.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel was born on November 14th of 1778 in Pressburg (now Bratislava). When he was eight, the family moved to Vienna. Like Mozart, he was a child prodigy: according to his father, he could read music at the age of four, and at the age of five he could play the piano and the violin very well. In 1786, Hummel was offered music lessons by none other than Mozart, who also housed him for two years, all free of charge. Even though Mozart was 22 years older than the boy, they played billiards and spent time together. At the age of nine Hummel performed one of Mozart’s piano concertos. Very much like Leopold Mozart, Hummel’s father took his child on a European tour. They ended up in London and stayed there for four years, Hummel taking lessons from Muzio Clementi. In 1791, Haydn, who knew the young Hummel from his visits to Mozart’s house in Vienna, was also staying in London; he dedicated a piano sonata to the boy, who performed it in public to great success. The French Revolution, the Terror and the subsequent wars changed the Hummels’s plans, and in 1793 they returned to Vienna. There Hummel continued taking music lessons, with Antonio Salieri and Joseph Haydn. One of Haydn’s pupils was Beethoven; the young men became friends. Hummel played at Beethoven’s memorial concert in 1827, and there he met Franz Schubert, who later dedicated his last three piano sonatas (some of the greatest piano music ever written) to Hummel.

In 1804 Hummel succeeded Haydn as the Kapellmeister to Nikolaus II, Prince Esterházy in Eisenstadt. He stayed there for seven years, returning to Vienna in 1811. After successfully touring Europe with his singer-wife and working in Stuttgart, Hummel settled in Weimar, being offered the position of the Kapellmeister at the Grand Duke’s court. He arrived there in 1819 and stayed for the rest of his life (Hummel died in 1837), making numerous touring trips in the meantime. He became friends with Goethe and turned the city into a major music center. At the court theater, he staged and conducted new operas by Weber, Rossini, Auber, Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Bellini. He also established one of the first pension plans for retired musicians, sometimes playing benefit concerts to replenish the funds. In 1832, Goethe died, Hummel’s health was failing, and he semi-retired, formally retaining his position of the Kapellmeister. Hummel died five years later.

During his lifetime, Hummel was one of the most celebrated pianists in the world and a very popular composer. He was also an important cultural figure, a music entrepreneur, and a famous, sought-after, and very expensive piano teacher. As a composer, he was a transitional figure between the Classical style and Romanticism. Even though he heavily influenced many composers of his time, Chopin and Schumann among them, nowadays Hummel’s music is mostly forgotten. He wrote operas, sacred music, many orchestral pieces, concertos, chamber music, and of course numerous piano pieces. Very little of it is still performed. Here’s Hummel’s Piano Sonata no. 4, Op.38. It’s played by the Korean pianist Hae-Won Chang.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: November 6, 2023. Rome, II. Classical Connect is still in Rome. On Saturday we went to a Santa Cecilia concert with Antonio Pappano conducting the Accademia's Orchestra and Igor Levit playing Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto. But we'd like to start with a decidedly non-musical detail. The Santa Cecilia Hall, inaugurated in 2002, was designed by the famous Italian architect, Renzo Piano. Many of Piano's pieces are airy and light, but not this one. It has little ambiance, despite the use of wood, and looks uninviting. The seating, which follows that of the Berliner Philharmonie, is placed all around the orchestra in shallow layers. We're not sure about the acoustics of the hall, as this was our first visit and we've never heard the Accademia Orchestra live, so it's not clear if the numerous imbalances (shrill winds, for example) are the orchestra's fault or the hall's.

But the most fascinating part of the hall's design is the men's bathroom. It has no urinals, only cabins. Men stand in line, not sure which cabin is empty, and enter one that's just vacated. When things get tough, they go around knocking on doors. The question is, were the urinals eliminated as a gesture of support for some feminist causes, or was Signor Piano not aware of how most men's toilets are usually (and efficiently) constructed?

But let’s get back to music. The program consisted of Cherubini’s Anacréon overture, Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto, Sibelius’s En Saga, and Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel.

Pappano’s entrance was accompanied by thunderous applause. The wind’s first entrance in the Cherubini was not a happy event. Things got better as they moved along, but even though Beethoven rated Cherubini highly, it’s little surprise that his music is played rarely these days.

Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto was a very different story. Igor Levit was superb. His technique seems to have improved since the last time we heard him in Chicago, and his command of the piece was total, even if one may disagree with some of his tempi. The performance was greeted ecstatically, and he played, exquisitely, an encore, Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118.

After the intermission, Pappano presented Sibelius with a speech and made the audience sing a tune from what was to follow. That was much more entertaining than the En Saga itself. The choice of the final piece, Till Eulenspiegel, would seem rather unusual, as the winds are not this orchestra's strong suit, but it went well, better than one might have expected judging by the three previous pieces.

If you add a hair-raising ride in a Roman taxi to the concert and back, this was, overall, quite an exhilarating event.Permalink

This Week in Classical Music: October 30, 2023. Rome, I. Classical Connect is in Rome this week, so this entry is short. Rome overwhelms visually: the sites, interiors of churches worthy of museums, and Roman museums, some of the best in the world. And of course, the magical Roman light. Aurally, things are very different: the usual cacophony of crowds and the ever-jammed traffic, the sirens of the police cars and ambulances trying to get through, and awful street musicians, strategically positioned where the largest crowds congregate but also wandering the streets, assailing the dining public with their renditions of the European schlagers of the 1980s.

Historically, Rome has always been one of the greatest musical centers of Europe, and there are dozens of places, from the Vatican to the palaces of the cardinals and nobility, that are linked to major musical events of the past, but sometimes these connections take a different shape, quite literally: the enormous Borghese palace, which is still the major residence of the family (part of the palazzo is occupied by the Spanish embassy) is nicknamed Il Cembalo, and its plan does look like a harpsichord, with the narrowest side facing the Tiber.

In the next couple of days, Antonio Pappano will be conducting the orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in a program of Cherubini, Beethoven (Piano Concerto no. 3 with Igor Levit), Sibelius and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel. The site classictic.com, which sells tickets online, decided that the composer of the last piece is Johann Strauss.

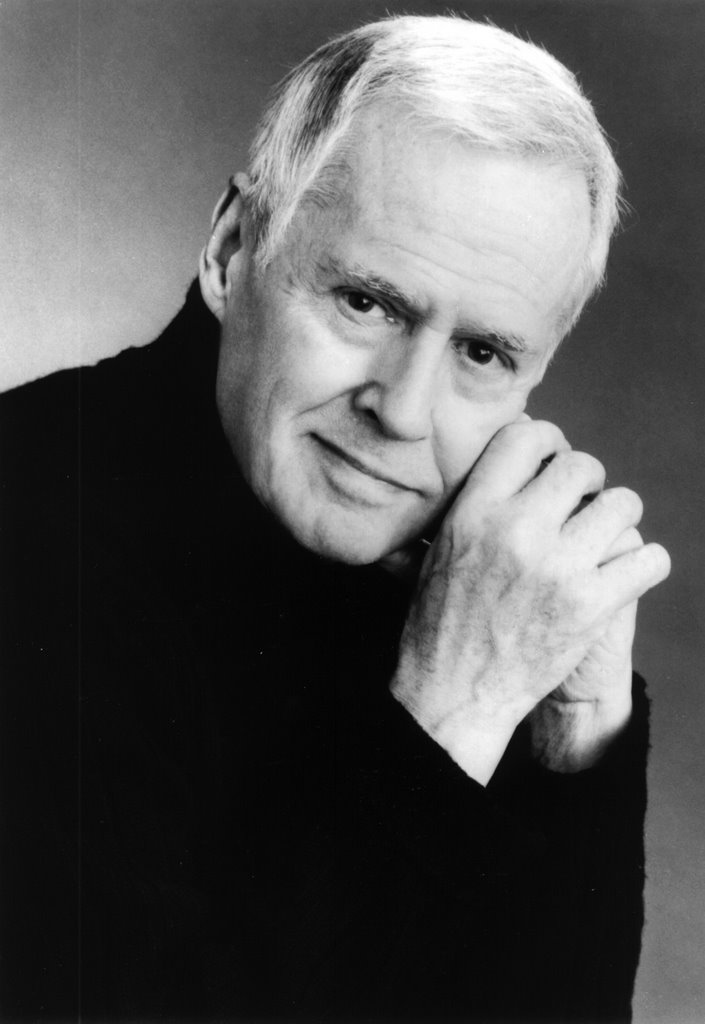

PermalinkThis Week in Classical Music: October 23, 2023. Short notes, II. Today is Ned Rorem’s 100th anniversary. Rorem died last year, just days short of his 99th birthday. He was a wonderful composer of songs and a whimsical writer. He spent almost a decade in France, where for a while he studied with Arthur Honegger (rather than Nadia Boulanger, as many American composers and pianists had done). In 1966 he published a book, Paris Diaries, based on his real diaries, full of gossip, gay stories, and a good read overall. In addition to about 500 art songs, some exceptionally good, he wrote two full-length operas, one of which, Our Town, based on a play by Thornton Wilder, was successfully staged in the US and abroad (he also wrote several smaller, one-act operas). In addition to that he composed three symphonies and a lot of piano music, including two concertos, but none of that music was as successful as his songs. Here is Rorem’s Sonnet. Susan Graham is accompanied by the pianist Malcolm Martineau and Ensemble Oriol.

composer of songs and a whimsical writer. He spent almost a decade in France, where for a while he studied with Arthur Honegger (rather than Nadia Boulanger, as many American composers and pianists had done). In 1966 he published a book, Paris Diaries, based on his real diaries, full of gossip, gay stories, and a good read overall. In addition to about 500 art songs, some exceptionally good, he wrote two full-length operas, one of which, Our Town, based on a play by Thornton Wilder, was successfully staged in the US and abroad (he also wrote several smaller, one-act operas). In addition to that he composed three symphonies and a lot of piano music, including two concertos, but none of that music was as successful as his songs. Here is Rorem’s Sonnet. Susan Graham is accompanied by the pianist Malcolm Martineau and Ensemble Oriol.

If Rorem wrote about 500 art songs, Domenico Scarlatti, who was born on October 26th of 1685, wrote more than 500 piano sonatas. They are mostly short, about as long as Rorem’s songs. Domenico was born in Naples, where his father, the renowned opera composer Alessandro Scarlatti, was working as maestro di capella at the court of the Spanish Viceroy of Naples. Though a thoroughly Italian composer, his link with Spain lasted throughout his life. He moved to Spain in 1729 and lived there for the remaining 25 years of his life.

Another Italian, Luciano Berio, was also born this week, on October 24th of 1925. He was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. You can read more about him here.

Niccolo Paganini and Georges Bizet both had their anniversaries this week, as did a minor but talented Russian composer of liturgical music, Alexander Gretchaninov. Next year is his 160th anniversary, so we’ll dedicate a post to him.Permalink