Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

September 10, 2015. Announcement from Classical Connect. Lately you may have noticed that Adobe Flash has fallen out of favor with many browsers. Messages warning about security concerns or even outright bans prevent Flash-based systems from functioning properly. To make matters worse, Apple has had issues with Flash for a long time and has not supported it on its devices. The original Classical Connect Player was written using Flash: with so many built-in functions, we had no viable alternatives at the time. Now with other options available, we’ve decided to rewrite the Player. On September 9th, 2015 we switched to the new Player. If you experience problems accessing the site or using the Player on this day or later, please reload the site or do a “hard reload”: ctrl-F5.

The good news is that now Classical Connect will play on practically all available devices, from Windows-based to Android to Apple, whether desktops, laptops, tablets or mobile phones. So if you had tried the service and were disappointed that it didn’t work, please try again: you should now be able to access any of the approximately 7,000 recordings in our library on any device.

If you have any problems or concerns, please let us know. Just send us an email to cc_contact@classicalconnect.com and we’ll get back to you.

In the mean time, please enjoy the great music and the wonderful musicians.

The Classical Connect team

September 7, 2015. Chopin’s Nocturnes, part II. On this holiday weekend we’ll skip several important anniversaries (Antonin Dvořák; one of our all-time favorites Henry Purcell; William Boyce, another wonderful English composer; and Arvo Pärt – we’ll write about them at another time) and turn to the nocturnes by Frédéric Chopin. This is the second part of an article, which we started on July 13th. It is a testament to the changing musical tastes that we’ll have to compliment the performances by the young pianists from our library (Krystian Tkaczewski and Gabriel Escudero) with those of the masters (Pollini, Rubinstein, Richter, Barenboim, and Horowitz), borrowed from YouTube. Not that long ago Chopin’s nocturnes were among the most often played pieces in all of the piano repertory. Not that anybody today doubts that these are works of genius – they’re just not performed as often. In some sense it’s even better, as they sound fresher that way. ♫

we started on July 13th. It is a testament to the changing musical tastes that we’ll have to compliment the performances by the young pianists from our library (Krystian Tkaczewski and Gabriel Escudero) with those of the masters (Pollini, Rubinstein, Richter, Barenboim, and Horowitz), borrowed from YouTube. Not that long ago Chopin’s nocturnes were among the most often played pieces in all of the piano repertory. Not that anybody today doubts that these are works of genius – they’re just not performed as often. In some sense it’s even better, as they sound fresher that way. ♫

2 Nocturnes, op. 37

The two nocturnes published as op. 37 form a marvelous pair of contrasting major/minor key pieces. Published in 1840, they were also composed around that time. The latter of the two, that in G major, with its barcarolle rhythms, is believed to have been composed the previous year when Chopin accompanied George Sand to the island of Majorca. At one time, these two works were highly praised. Robert Schumann considered them the finest nocturnes Chopin composed describing them as “of that nobler kind under which poetic ideality gleams more transparently (than the earlier Nocturnes).” However, since the twentieth century, this praise has somewhat waned.

The first of the op. 37 nocturnes is in G minor (here). Its lugubrious melody is modestly ornamented and unfolds expressively over a chordal accompaniment in steady quarter notes. It is immediately restated, with some further ornamentation, but greatly intensified as the dynamic is raised from piano to forte, and even reaches fortissimo. Yet, Chopin reigns in the melody’s emotional outpouring with a softer dynamic at the start of its second strain, leaving it to carry on in hushed torment until its conclusion. From a closing cadence in the tonic key, Chopin modulates with ease into the key of E-flat major for the consoling middle portion. This entire episode takes on the character of a simple, pious choral, which some commentators interpret as an expression of Chopin’s faith in religion. With the exception of a few grace notes, the quarter note rhythm is undisturbed, carrying the music along with unshakeable surety. Indeed, there is an effortless serenity here in Chopin’s music. During its last measures, the chorale is broken up by pauses, and subtle changes in harmony lead to reestablishment of the key of G minor. The opening melody is then reprised and is virtually unchanged, albeit shortened, and its final measures are altered to bring about an effective close on the tonic major chord. (Continue reading here).Permalink

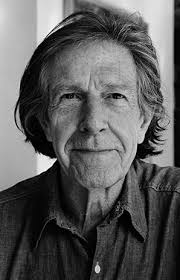

Bruckner, while a composer of genius, was sometimes verbose and repetitive. It’s difficult to imagine somebody more different than our next composer, John Cage, who is famous (or infamous, in the eyes of some) for his 4’33’’, which is “performed” without a note being played. (It’s often assumed that the point of this piece is four minutes and 33 seconds of silence; Cage was actually interested in the ambient sounds of the concert hall). John Cage was born on September 5th of 1912 in Los Angeles. He studied composition with Henry Cowell and later, in 1934, with Arnold Schoenberg. During the following 15 years he composed mostly in the 12-tone mode, writing music for different percussion ensembles (much of it in collaboration with his friend, the choreographer Merce Cunningham) and, eventually, the prepared piano (the piano is “prepared” by placing different objects between the strings, thus changing its sound). In 1949 he traveled to Europe and met Olivier Messiaen and the young Pierre Boulez who became a good friend. Six Melodies for violin and electronic piano (here) written in 1950 are from the end of that period. In the early 1950s, Cage, together with Morton Feldman, embarked on a completely new path: they introduced chance, or randomness, into the process of composing. Cage first employed it in the Concerto for Prepared Piano and orchestra: he created a set of sonorities for both the piano and the orchestra, but the sequencing of these sets were completely random and up to the musicians. To support the chance technique, Cage had to come up with his own notational principles. Some of them involved transparencies that could be mixed and matched to create the final score. The majority of the public was not convinced, and even some of the modernist composers, such as Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen heavily criticized this approach. Iannis Xenakis called it an abuse of (musical) language and an abrogation of the composer's function. Nonetheless, Cage’s influence, and even fame, were spreading, both in the US and even more so in Europe. His work with the popular Cunningham Dance Company helped in this respect. Cage continued his chance-based composition using more and more unusual instruments: one of them directed performers to mount and play 88 tape loops on several tape recorders. Cage is probably an acquired taste, but he was very influential as a composer who altered our approach to sound and modern definition of music itself. Cage continued to compose and experiment almost to the end of his life. He died in New York on August 12th of 1992.

Bruckner, while a composer of genius, was sometimes verbose and repetitive. It’s difficult to imagine somebody more different than our next composer, John Cage, who is famous (or infamous, in the eyes of some) for his 4’33’’, which is “performed” without a note being played. (It’s often assumed that the point of this piece is four minutes and 33 seconds of silence; Cage was actually interested in the ambient sounds of the concert hall). John Cage was born on September 5th of 1912 in Los Angeles. He studied composition with Henry Cowell and later, in 1934, with Arnold Schoenberg. During the following 15 years he composed mostly in the 12-tone mode, writing music for different percussion ensembles (much of it in collaboration with his friend, the choreographer Merce Cunningham) and, eventually, the prepared piano (the piano is “prepared” by placing different objects between the strings, thus changing its sound). In 1949 he traveled to Europe and met Olivier Messiaen and the young Pierre Boulez who became a good friend. Six Melodies for violin and electronic piano (here) written in 1950 are from the end of that period. In the early 1950s, Cage, together with Morton Feldman, embarked on a completely new path: they introduced chance, or randomness, into the process of composing. Cage first employed it in the Concerto for Prepared Piano and orchestra: he created a set of sonorities for both the piano and the orchestra, but the sequencing of these sets were completely random and up to the musicians. To support the chance technique, Cage had to come up with his own notational principles. Some of them involved transparencies that could be mixed and matched to create the final score. The majority of the public was not convinced, and even some of the modernist composers, such as Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen heavily criticized this approach. Iannis Xenakis called it an abuse of (musical) language and an abrogation of the composer's function. Nonetheless, Cage’s influence, and even fame, were spreading, both in the US and even more so in Europe. His work with the popular Cunningham Dance Company helped in this respect. Cage continued his chance-based composition using more and more unusual instruments: one of them directed performers to mount and play 88 tape loops on several tape recorders. Cage is probably an acquired taste, but he was very influential as a composer who altered our approach to sound and modern definition of music itself. Cage continued to compose and experiment almost to the end of his life. He died in New York on August 12th of 1992.

August 27, 2015. Bruckner, Cage and many more. Several great – or at least interesting – composers were born this week: Johann Pachelbel, Pietro Locatelli, Anton Bruckner, Darius Milhaud, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Amy Beach and John Cage. Anton Bruckner, who was born on September 4th, 1824, clearly belongs to the former category, and even though we’ve wrotten about him extensively before, we cannot neglect his anniversary. This time we’ll present his Symphony no. 4 in its entirety (when we wrote about Bruckner three years ago, we played just the third movement, Scherzo). Bruckner created many versions of this symphony: he wrote the first version in 1874, then in 1878, after completing the Fifth symphony, he returned to the Fourth, revised the first two movements and completely rewrote the finale. He continued tinkering with it for several more years, and then significantly revised it again in 1887. One year later he made more changes – altogether there are seven versions, of which three are considered “principal.” We’ll hear the second of these. Claudio Abbado leads the Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

And now as a respite from Cages’ musical experiments, something much more conventional: music by Pietro Locatelli, who was born on September 3rd of 1695 in Bergamo. An Italian Baroque composer and violinist, he wrote a number of very pleasing, if not necessarily revolutionary, compositions. Here’s one of them, his Violin Concerto in C minor op. 3. Luca Fanfoni is the soloist with the Reale Concerto.Permalink

August 24, 2015. A concert at the Steans. The 2015 season at the Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute is over, and we’ve uploaded some of the recordings made at their concerts. Every year the Steans, which is Ravinia’s summer conservatory, brings to this Chicago suburb a group of talented young musicians. They study with some of the most renowned teachers, and also perform: the Steans concerts are the highlight of the season. The students play solo recitals and make music together, in ad hoc trios, quartets, and even octets – some of these temporary ensembles achieve very high level of musicianship (it goes without saying that technically all of them play at a very high level). And that’s how the first concert of the 2015 season was programmed: Leonardo Hilsdorf, a young Brazilian pianist, played Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata in F Minor, K. 466 and five string players performed Mozart’s String quintet no. 4. But the most interesting and in a way quite unique part of the program was the set of Twelve Caprices for viola solo by Atar Arad. Mr. Arad, who is 70, is a world-renowned viola player; he taught at the Steans for a number of years. He was born in Tel-Aviv and started out as a violinist before switching to the viola in 1971. As a youngster he won several international competitions and made a number of highly praised recordings. In 1980 he moved to the US and joined the Cleveland Quartet. He’s also collaborated with the leading musicians of our time, among them the pianists Eugene Istomin and Emanuel Ax, violist Jaime Laredo and the cellists Yo-Yo Ma and Mstislav Rostropovich. He started composing rather late, publishing his first work in 1992 (Solo Sonata for Viola). His Twelve Caprices for viola solo were composed in 2003. During the first Steans concert, several violists took turns playing all twelve. Mr. Arad played one of them. Here’s the First caprice, performed by the Russian violist Georgy Kovalev. The Third Caprice is played by Mr. Arad, and Caprice no. 11 – by Dana Kelley (here).

They study with some of the most renowned teachers, and also perform: the Steans concerts are the highlight of the season. The students play solo recitals and make music together, in ad hoc trios, quartets, and even octets – some of these temporary ensembles achieve very high level of musicianship (it goes without saying that technically all of them play at a very high level). And that’s how the first concert of the 2015 season was programmed: Leonardo Hilsdorf, a young Brazilian pianist, played Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonata in F Minor, K. 466 and five string players performed Mozart’s String quintet no. 4. But the most interesting and in a way quite unique part of the program was the set of Twelve Caprices for viola solo by Atar Arad. Mr. Arad, who is 70, is a world-renowned viola player; he taught at the Steans for a number of years. He was born in Tel-Aviv and started out as a violinist before switching to the viola in 1971. As a youngster he won several international competitions and made a number of highly praised recordings. In 1980 he moved to the US and joined the Cleveland Quartet. He’s also collaborated with the leading musicians of our time, among them the pianists Eugene Istomin and Emanuel Ax, violist Jaime Laredo and the cellists Yo-Yo Ma and Mstislav Rostropovich. He started composing rather late, publishing his first work in 1992 (Solo Sonata for Viola). His Twelve Caprices for viola solo were composed in 2003. During the first Steans concert, several violists took turns playing all twelve. Mr. Arad played one of them. Here’s the First caprice, performed by the Russian violist Georgy Kovalev. The Third Caprice is played by Mr. Arad, and Caprice no. 11 – by Dana Kelley (here).

For those who would rather listen to something more traditional, here’s the above-mentioned Sonata by Domenico Scaralli, and hear – the Mozart.Permalink

August 17, 2015. Claude Debussy. Several composers were born this week, among them Antonio Salieri and Georges Enesco, but of course all of them are overshadowed by Claude Debussy. Before we turn to Debussy, though, we want to mention Nicola Porpora. A Baroque opera composer and teacher of the famous castrato Farinelli and also of Franz Joseph Haydn, Porpora was born on this day in 1686. He is almost forgotten these days, not entirely deservedly, as you can judge for yourself by this aria from his opera Polifermo. Philippe Jaroussky is the countertenor. Now back to Debussy.

Claude Debussy was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, on August 22nd, 1862, the eldest of five children. His father owned a shop selling china and crockery and his mother was a seamstress. In 1867, the family moved to Paris but when the Franco-Prussian war broke out a few years later in 1870, his mother sought refuge with an in-law in Cannes. While there, Debussy began to take piano lessons from a local elderly Italian violinist. He progressed rapidly on the instrument and his talent for music soon became quite evident. Two years later, in 1872, at the age of ten, he was enrolled in the prestigious Paris Conservatoire.

eldest of five children. His father owned a shop selling china and crockery and his mother was a seamstress. In 1867, the family moved to Paris but when the Franco-Prussian war broke out a few years later in 1870, his mother sought refuge with an in-law in Cannes. While there, Debussy began to take piano lessons from a local elderly Italian violinist. He progressed rapidly on the instrument and his talent for music soon became quite evident. Two years later, in 1872, at the age of ten, he was enrolled in the prestigious Paris Conservatoire.

Debussy spent eleven years at the Conservatoire and studied with some of the leading musicians of France. Despite his talent, however, Debussy was headstrong and showed a stubborn preference for the unusual and experimental. His early compositions often drew the ire of his professors and were heavily criticized for his apparent disregard of the Conservatoire’s teaching. Nevertheless, in 1884, Debussy won the Prix de Rome with his composition L’enfant prodigue and the following year he left for the Villa Medici in Rome to continue his studies. According to his letters, Debussy found the artistic and cultural atmosphere of Rome stifling. He eventually composed four pieces, however, the most notable among them being the cantata La demoiselle élue. The work drew sharp criticism from the French Academy who called it “bizarre.” It is, however, the first piece to give a glimpse of Debussy’s emerging mature style.

During 1888-9, Debussy traveled to Bayreuth and was for the first time exposed to Wagner’s operas. Like many other young musicians of the time, he was inspired by Wagner’s overt emotionalism, striking harmonies and handling of musical form. Around this time, he also found a like spirit in Eric Satie, who shared Debussy’s experimental approach to composition. By the 1890s, the infatuation with Wagner’s music had subsided and Debussy mature style began to take a more definite form. This style was greatly influenced by the Symbolist movement in the visual and literary arts, which developed as a revolt against realism and the heroic imagery of Romanticism. Symbolism influenced him more than the music of other composes, although, in addition to Wagner, he found inspiration in the music of Russia, particularly from “The Five.”

In 1894, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, a symphonic poem based on a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, premiered in Paris. Considered controversial at the time, the piece was later responsible for establishing Debussy as one of the leading composers of the burgeoning Modern era. Later, in 1902, after ten years of work, he produced his only opera, Pelléas et Mélisande. It premiered at the Opéra-Comique in April of that year and was an immediate success. With his fame growing, Debussy was engaged as a conductor throughout Europe mainly performing his own works, including his multi-movement work La Mer.

Debussy died on March 25th, 1918 from cancer amidst German aerial and artillery bombardment of Paris during World War I. Because of the fighting, it was impossible to hold a public funeral for one of France’s leading artistic figures and consequently his funeral procession made its way through abandoned streets as German artillery shells exploded throughout the city. His music went on to inspire some the leading composers of the 20th century, among theme Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky and Olivier Messiaen, as well as musicians in jazz, such as George Gershwin and Duke Ellington.

We have almost 200 recording of Debussy’s work, so browse our library and you’ll find something you like. In the mean time, here are Estampes, performed by the pianist Katsura Tanikawa. Permalink

August 10, 2015. Five French composers. We missed some interesting anniversaries last week and several more are coming in the next several days. Out of these we’ve selected a group of composers that have two things in common: all of them are French and all were born within 50 years in the second half of the 19th century or early in the 20th. They are, in chronological order, Cécile Chaminade, Gabriel Pierné, Reynaldo Hahn, Jacques Ibert and André Jolivet. While none of them reached the level of Debussy or Ravel, all were very talented.

Cécile Chaminade, the only woman in this group, was born on August 8th of 1857 in Paris. Her first music lessons came from her mother, a pianist and a singer. Later she studied composition with Benjamin Godard. She started composing very young (when she was eight, she played some music for Georges Biset) and gained prominence with the publication of Piano Trio in 1880. An excellent pianist, she toured England many times, playing mostly her own music and became very popular there. In 1908 she went to the US, the country of “Caminade fan clubs” and played in 12 cities. Between 1880 and 1890 Chaminade composed several large orchestral compositions and also music for piano and orchestra. In the following period she scaled down, limiting herself to piano character pieces, of which she wrote more than 200. Many of them are charming though they became dated even during her time (Chaminade lived till 1944). Here’s her Automne, it’s performed by the British-Canadian pianist Valerie Tryon.

first music lessons came from her mother, a pianist and a singer. Later she studied composition with Benjamin Godard. She started composing very young (when she was eight, she played some music for Georges Biset) and gained prominence with the publication of Piano Trio in 1880. An excellent pianist, she toured England many times, playing mostly her own music and became very popular there. In 1908 she went to the US, the country of “Caminade fan clubs” and played in 12 cities. Between 1880 and 1890 Chaminade composed several large orchestral compositions and also music for piano and orchestra. In the following period she scaled down, limiting herself to piano character pieces, of which she wrote more than 200. Many of them are charming though they became dated even during her time (Chaminade lived till 1944). Here’s her Automne, it’s performed by the British-Canadian pianist Valerie Tryon.

Gabriel Pierné was born in Metz, Lorraine on August 16th, 1863. In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian war, Metz was captured by the Germans, and the Piernés fled to Paris. Gabriel entered the Paris Conservatory, where among his teachers were Jules Massenet (composition) and Cesar Frank (organ). In 1910 Pierné, who was also a prominent conductor, let the orchestra during the premier of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, which was staged by the Ballet Russes. His own music was not as adventuresome: it was influenced by Camille Saint-Saëns and, to alesser degree, Debussy and Ravel. Here’s the first movement (Allegretto) of Pierné’s Sonata op.36 for violin and piano. The young French violinist Elsa Grether is accompanied by Eliane Reyes on the piano.

Reynaldo Hahn wasn’t French by birth but he took on the French nationality later in his life. He was born in Caracas, Venezuela, on August 9th of 1874. His father was a German-Jewish engineer, his mother came from a Spanish family. When Reynaldo, the youngest of 12 children, was four, the family moved to Paris. In 1885 Hahn entered the Paris Conservatory, where one of his teachers was the same Jules Massenet. At the Conservatory Hahn befriended Ravel and Cortot, and through them, many writers and musicians. A closeted homosexual, Hahn met a young writer, Marcel Proust in 1894; they became good friends and lovers. Hahn is best known for his wonderful songs, but that wasn’t his only creative genre. Between 1902 and 1902 he wrote 53 “Poèmes pour piano,” which he collected under the title of Le Rossignol Éperdu (The Distraught Nightingale). Here’s the piece no. 37, L'Ange Verrier (The glass Angel); it’s performed by the pianist Earl Wild.

Jacques Ibert, probably the most popular of the five, was born on August 15th of 1890. We’ve written about him a number of times, so to commemorate we’ll play his Concertino da Camera for Alto Saxophone and Eleven Instruments from 1935, transcribed for saxophone and piano. Xavier Larsson Paez is on the saxophone, with Yoko Yamada-Selvaggio on the piano.

André Jolivet is the youngest and the most adventuresome of the five. He was born on August 8th of 1905 in Paris. In his childhood he studied the cello but never went to the conservatory (he did study composition with Paul Le Fem, a composer and critic). In his youth Jolivet was influenced by Debussy and Ravel, but it all changed when he became familiar with atonal music: in December of 1927 he attended a concert at the Salle Pleyel during which several Schoenberg piece were performed and that changed his life. Soon after he became a pupil of Edgard Varèse, an influential French-American avant-garde composer. He also befriended Olivier Messiaen, who, being better known in those years, helped Jolivet by promoting his music. We’ll Jolivet’s Concerto pour Ondes Martenot. Ondes Martenot (Waves of Martenot) is an early electronic instrument, invented in 1928 by Maurice Martenot. The soloist in this recording is Jeanne Loriod, the sister of Yvonne Loriod, the second wife of Messiaen. The composer conducts the Orchestre Philharmonique de l`ORTF.Permalink