Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

October 27, 2014. Paganini and Berio. Today is the birthday of Niccolò Paganini, who was born in Genoa in 1782. As a composer he’s best known for his 24 caprices for violin solo and several violin concertos. So here, to celebrate, are two caprices, played by two of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, David Oistrach (caprice no. 17, recorded in 1946) and Jascha Heifetz (Caprice no. 13, in a somewhat unnecessary arrangement for the violin and piano, with Brooks Smith, recorded in 1956).

Last week we wrote about Liszt’s first book of Années de pèlerinage and didn’t have time to mark the 89th birthday of the Italian composer Luciano Berio, who was born on October 24th of 1925. Berio was one of the most interesting composers of the second half of the 20th century. Born into a musical family (both his father and grandfather were organists and composers) he started studying music at an early age. During the war he was conscripted by Mussolini’s Republic of Salò, but injured himself in training and spent most of the time in a hospital. When the war was over, he went to Milan to study piano and composition but his injured hand cut short his piano aspirations. His early compositions were written in the neo-classical style of the Stravinsky type, but he soon became interested in the avant-garde music and especially in serialism. In 1952 he went to the US to study with Luigi Dallapiccola in Tangelwood. Dallapiccola, also an Italian, was the major proponent of serialism, being influenced by Webern and Berg.

Berio then attended several of the International summer courses in Darmstadt, at that time the epicenter for new music in Europe. Darmstadt was the place for young composers and music theoreticians to listen to music, lecture, argue, and share ideas. Among the participants were Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti, Milton Babbit, Hanz Werner Henze and many others. Theodor Adorno, the leading philosopher and musicologist, was one of the active participants. In the 1960s Berio spent a lot of time in the US, teaching at Tanglewood and Juilliard. Interested in electronic music, he went to Paris and became a co-director of IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique), a place associated with the name of Pierre Boulez and one of the leading centers of research in new music in general and electro-acoustical music in particular. After returning to Italy in the 1980s, Berio created a similar center in Florence, called Tempo Reale. Though he was a sought-after teacher and traveled constantly, he bought some land and buildings in the village of Radicondoli, not far from Siena. That became his base, especially after his third marriage to Talia Pecker, an Israeli musicologist. Berio continued to actively travel, conduct and compose till the end. He died in Rome on May 27, 2003.

Berio possessed a wonderful intellectually curiosity which went well beyond music. In the 1950s he collaborated with Umberto Eco, a philosopher, novelist and literary critic. Together they produce several radio programs on language and sound - for example, words that are formed by sounds that describe their meaning (like “cuckoo,” for example, or “roar”; the fancy name for it is “onomatopoeia”). Eco also got Berio interested in semiotics, the study of symbols and signs. Later in his life Berio collaborated with the writer Italo Calvino and the architect Renzo Piano.

Berio worked in many different styles, from pieces for solo instruments to orchestral works for operas. He wrote a series of works for different instruments calls Sequenza. The first Sequenza, for flute, was written in 1956, the last Sequenza XIV, for cello, in 2002. From 1950 to 1964 Berio was married to Cathy Berberian, an American mezzo-soprano (they met in Milan, while studying at the conservatory). Sequenza III, for voice, written in 1965, and dedicated to her. And here she is, singing this piece. Berio’s Sinfonia was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered in 1968. Here’s the first movement, performed by the Orchestre National de France under direction of Pierre Boulez, with and the Swingle Singers, 1969.Permalink

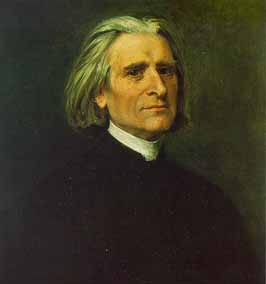

October 20, 2014. Franz Liszt. We’re marking the 113th birthday anniversary of the great Hungarian composer. Liszt was born on October 22nd of 1811 in a small village of Doborján (after the First World War that part of western Hungary was given to Austria; the town is now called Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

Raiding). He grew up to become the greatest pianist of his time (and some believe of all time) and one of the most important composers of the 19th century. To celebrate, we‘re publishing an article by Joseph DuBose on the first of the three Années de pèlerinage piano suites, Première année: Suisse. We illustrate each piece (there are nine altogether in Première année) with performances by two young English pianists, Ashley Wass and Sodi Braide, both recorded in concerts, and two great Lisztians, the Cuban-American Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) and the Russian pianist Lazar Berman (1930 – 2005). The article follows. ♫

In early June 1835, Franz Liszt traveled from Paris to Switzerland. There, in Geneva, he met his mistress, Marie d’Agoult, who had recently left her husband and family for him. Over the next four years, they lived and journeyed throughout Switzerland and Italy. Inspired by the wondrous scenery of Switzerland and the rich cultural heritage of Italy, Liszt composed during these years a suite of piano pieces entitled Album d’un voyageur, a title which he likely adapted from that of a letter from George Sand: Lettre d’un voyageur. The suite was later published in 1842, after his relationship with d’Agoult had ended and he had returned to the life a touring virtuoso. However, Album would prove to be only the genesis of a much more significant collection of pieces. Between 1848 and 1854, Liszt revised several of its constituent pieces to form the first volume (Première année: Suisse) of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage)—indeed, only two emerged relatively unaltered. Besides being personal reflections of Liszt’s travels, the pieces that ultimately became part of Première année were imbued with a keen sense of the Romantic literature of his time. The title of Années de pèlerinage itself is a certain reference to Goethe’s famous novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahr, but mostly significantly, its sequel Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahr, which in is first French translation was translated as “Years of Wanderings.” Furthermore, each piece was headed by quotations from Schiller, Byron, and Senancour, leading figures of the burgeoning Romantic Movement. The final result, Première Année: Suisse, was published in 1855. (Continue reading here.)Permalink

October 13, 2014. Jacob Obrecht. We’ve never written about Jacob Obrecht, which is quite an omission, as he was one of the most famous composers of his time. Obrecht was born in 1457 or 1458, which makes him an almost exact contemporary of Josquin des Prez. Obrech was born in Ghent, one of most important cities in Flanders, which were then ruled by the Dukes of Burgundy (Josquin, on the other hand, was born in the county of Hainaut, about 100 miles south of Ghent. Hainaut was also ruled by the Burgundians but was a French-speaking county, whereas in Ghent Flemish was spoken). Obrecht’s father was the city trumpeter who also played at the court. It seems that Jacob was close to his father: upon his death he wrote a motet, Mille Quingentis, in his honor (here, performed by The Clerks' Group). It’s likely that Jacob also played the trumpet and that his father introduced him to the court, where he would’ve met Antoine Busnois, the favorite composer of Charles the Bold (some musicologists discern the influence of Bunois in Obrecht’s masses). Obrecht achieved fame early in his life: in the treaties published in mid-1480s, Johannes Tinctoris, a composer and music theorist, mentions him among the most renowned composer of the century; at that time Obrecht wasn’t even 30 years old. In 1484 Obrecht assumed the position of choirmaster at the Cambrai cathedral (famous at its time, the cathedral was destroyed during the French Revolution, the same fate asso many other old churches). He didn’t stay there for long, however: just one year later he was accused of embezzling money from the cathedral and had to leave. He went to Bruges, where he found a similar position. Two years later, in 1487, Duke Ercole d'Este I of Ferrara invited him to his court, and he stayed for almost a year. Obrecht was dismissed from his post in Bruges in 1490 (the reason for which we don’t know) and for the following 14 years he moved from one city in Flanders to another – Antwerp, Bergen, then Bruges again – working in the cathedrals and composing. In 1504 he returned to Ferrara, hired by his enthusiastic patron, Duke Ercole. In Ferrara he replaced Josquin, who left the city probably to escape an outbreak of the plague. Obrecht’s stay in Ferrara wasn’t long. In June of 1505 the Duke died. Obrecht tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain a position in Mantua where the ruler, Francesco II Gonzaga, was married to Isabella d'Este, the daughter of Ercole and whose court was famous as a cultural and music center. Obrecht remained in Ferrara and a couple of months later yet another outbreak of the plague caught up with him; he died on August 1st of 1505. He wasn’t even 50 years old.

Burgundy (Josquin, on the other hand, was born in the county of Hainaut, about 100 miles south of Ghent. Hainaut was also ruled by the Burgundians but was a French-speaking county, whereas in Ghent Flemish was spoken). Obrecht’s father was the city trumpeter who also played at the court. It seems that Jacob was close to his father: upon his death he wrote a motet, Mille Quingentis, in his honor (here, performed by The Clerks' Group). It’s likely that Jacob also played the trumpet and that his father introduced him to the court, where he would’ve met Antoine Busnois, the favorite composer of Charles the Bold (some musicologists discern the influence of Bunois in Obrecht’s masses). Obrecht achieved fame early in his life: in the treaties published in mid-1480s, Johannes Tinctoris, a composer and music theorist, mentions him among the most renowned composer of the century; at that time Obrecht wasn’t even 30 years old. In 1484 Obrecht assumed the position of choirmaster at the Cambrai cathedral (famous at its time, the cathedral was destroyed during the French Revolution, the same fate asso many other old churches). He didn’t stay there for long, however: just one year later he was accused of embezzling money from the cathedral and had to leave. He went to Bruges, where he found a similar position. Two years later, in 1487, Duke Ercole d'Este I of Ferrara invited him to his court, and he stayed for almost a year. Obrecht was dismissed from his post in Bruges in 1490 (the reason for which we don’t know) and for the following 14 years he moved from one city in Flanders to another – Antwerp, Bergen, then Bruges again – working in the cathedrals and composing. In 1504 he returned to Ferrara, hired by his enthusiastic patron, Duke Ercole. In Ferrara he replaced Josquin, who left the city probably to escape an outbreak of the plague. Obrecht’s stay in Ferrara wasn’t long. In June of 1505 the Duke died. Obrecht tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain a position in Mantua where the ruler, Francesco II Gonzaga, was married to Isabella d'Este, the daughter of Ercole and whose court was famous as a cultural and music center. Obrecht remained in Ferrara and a couple of months later yet another outbreak of the plague caught up with him; he died on August 1st of 1505. He wasn’t even 50 years old.

It is usually assumed that the more famous Josquin had influenced the music of Obrecht. It’s probably not so: much of Josquin’s mature work was written after 1505 (Josquin lived till 1521). The music of Johannes Ockeghem, on the other hand, did affect Obrecht’s compositional style. You can listen to three more pieces by Obrecht. The first one is Kyrie from his Missa Fortuna Desperata. It’s performed by the Anglo-German ensemble The Sound and the Fury (here). The second and the third pieces are the identically named motets, Salve regina. The first one is for four voices (here), and the second, an absolutely magnificent one – for six voices (here). Both are performed by the Oxford Camerata, Jeremy Summerly conducting.

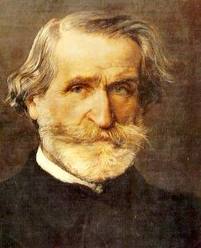

PermalinkOctober 6, 2014. Verdi and Saint-Saëns. Several composers were born this week, Giuseppe Verdi being the most important one. Verdi was born on October 9th of 1813 and last year we celebrated his centenary, writing about his four immensely popular operas, Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Don Carlos, almost as popular, was one of Verdi’s late operas (as were, for example, Aida and Otello). It was commissioned by the Paris Opera in 1866. Five years earlier, in 1861, following Garibaldi’s expeditions, large parts of Italy were united and Victor Immanuel II was crowned the King of Italy. And earlier in1866 Italy fought another war of independence with Austria-Hungary; it stared badly but thanks to the simultaneous (and utterly disastrous) war that Austria was fighting with Prussia, Italy emerged victorious. Venice was joined with the rest of Italy and the Italian state came into being practically in its modern form. Italian nationalism flourished and Verdi was at the epicenter of it. By then he was the most famous opera composer in Europe and the most famous person in Italy. It’s said that letters addressed just “G. Verdi” were delivered to him without fail. At the end of every performance of his operas, the public would stand up and shout “Viva Verdi!” and then continue celebrating him on the streets.

writing about his four immensely popular operas, Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, and Aida. Don Carlos, almost as popular, was one of Verdi’s late operas (as were, for example, Aida and Otello). It was commissioned by the Paris Opera in 1866. Five years earlier, in 1861, following Garibaldi’s expeditions, large parts of Italy were united and Victor Immanuel II was crowned the King of Italy. And earlier in1866 Italy fought another war of independence with Austria-Hungary; it stared badly but thanks to the simultaneous (and utterly disastrous) war that Austria was fighting with Prussia, Italy emerged victorious. Venice was joined with the rest of Italy and the Italian state came into being practically in its modern form. Italian nationalism flourished and Verdi was at the epicenter of it. By then he was the most famous opera composer in Europe and the most famous person in Italy. It’s said that letters addressed just “G. Verdi” were delivered to him without fail. At the end of every performance of his operas, the public would stand up and shout “Viva Verdi!” and then continue celebrating him on the streets.

The libretto of Don Carlos, which is loosely based on a play by Friedrich Schiller, was written in French. The opera was premiered on March 11, 1867 in the beautiful Salle Le Peletier, which housed the Paris Opera till a fire burned it down in 1873 and the company had to move to the newly built Palais Garnier just a couple blocks away. The story revolves around Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias, whose proposed bride, Elisabeth de Valois, marries the prince’s father, Philip II the King of Spain, instead. As always in Verdi’s opera, there are many additional complications, with Princess Eboli falling in love with Carlos, the heretics being put to death, and the politics of Flanders also playing a role. The opera turned out to be too long, even in Verdi’s own estimation, and he began to paring it down ahead of the premier in Paris. Later the same year Verdi created an Italian version of the Don Carlos (called Don Carlo) for the opera theater in Bologna. This is one of the rare operas that rightfully exist in two different languages. Verdi continued revising Don Carlos and several versions exist in both languages. These days it’s performed more often in Italian, but wonderful French-language recordings exist as well: one, for example, with a phenomenal cast that is headed by Placido Domingo as Carlos, with Katia Ricciarelli as Eizabeth, Lucia Valentini Terrani as Eboli, Leo Nucci as Rodrigue (Rodrigo in the Italian version), Ruggero Raimondi as King Philip II and Nicolai Ghiaurov as the Grand Inquisitor. Luciano Pavarotti as Carlo, Daniela Dessì as Elisabetta and Samuel Ramey as the King, with Riccardo Muti conducting, made a great recording of the Italian version in 1992.

A grand dramatic work, Don Carlos may not be as packed with great arias as, for example, Rigoletto, but it has its share of sublimely beautiful music. Here Samuel Ramey sings Ella giammai m'amò! from Act IV of the famous recording we mentioned above. Riccardo Muti leads the orchestra and the chorus of the Teatro alla Scala, Milan. And here Maria Callas sings Tu che le vanita from Act V in a 1959 concert performance in Hamburg. Send shivers down one’s spine, doesn’t it? Lastly, Carlo Bergonzi as Don Carlo and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Rodrigo sing the duet E lui! desso! L'infante!... Dio che nell'alma infondere...from Act II with the London Royal Opera House orchestra under the baton of Georg Solti (here, in a 1965 recording).

Camille Saint-Saëns was also born on the 9th, in 1835 and usually gets a short shift. We promise to write more on him next year. Permalink

William Boyce was born in London, shortly before September 11th of 1711 (he was baptized that day). He was admitted to the St. Paul Cathedral as a choirboy at the age of eight and studied there with Maurice Greene (even though Greene was 15 years older than Boyce, they eventually became good friends). In 1734 Boyce was hired as the organist at the Oxford Chapel in London; it was around that time that he published his first compositions. A virtuoso organist, he worked in many churches in London. In early 1740 he composed a “serenata” called Solomon – in reality a full-blown oratorio running for more than an hour. It became popular (some say almost as popular as Handel’s Messiah), establishing Boyce as a first-rank composer. In 1747 he composed Twelve Sonatas for Two Violins and a Bass¸ that were also met with acclaim (you can listen to Sonata no. 1, performed by Collegium Musicum 90, here). A highlight of his career was the performance, in Cambridge on July of 1749, of his celebratory ode during the installation of the Duke of Newcastle as the Chancellor of the University. Here’s the Overture to the Ode, Here all thy active fires diffuse, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Raymond Leppard. In 1755, following Maurice Greene’s death, he was appointed the Master of the King's Music (or Musick, as it was spelled back then). Three years later came another honor, his appointment as the organist to the Chapel Royal. In 1760 Boyce published a collection of his eight symphonies, written during the previous 20 years. A year later he composed music for the wedding of George III to Princess Charlotte, The King Shall Rejoice (here, with the choir of the New College Oxford and the Academy of Ancient Music, Edward Higginbottom conducting). He semi-retired soon after, living in Kensington Gore next to Hyde Park in London and composing occasional pieces. William Boyce died on February 7th of 1779.

William Boyce was born in London, shortly before September 11th of 1711 (he was baptized that day). He was admitted to the St. Paul Cathedral as a choirboy at the age of eight and studied there with Maurice Greene (even though Greene was 15 years older than Boyce, they eventually became good friends). In 1734 Boyce was hired as the organist at the Oxford Chapel in London; it was around that time that he published his first compositions. A virtuoso organist, he worked in many churches in London. In early 1740 he composed a “serenata” called Solomon – in reality a full-blown oratorio running for more than an hour. It became popular (some say almost as popular as Handel’s Messiah), establishing Boyce as a first-rank composer. In 1747 he composed Twelve Sonatas for Two Violins and a Bass¸ that were also met with acclaim (you can listen to Sonata no. 1, performed by Collegium Musicum 90, here). A highlight of his career was the performance, in Cambridge on July of 1749, of his celebratory ode during the installation of the Duke of Newcastle as the Chancellor of the University. Here’s the Overture to the Ode, Here all thy active fires diffuse, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Raymond Leppard. In 1755, following Maurice Greene’s death, he was appointed the Master of the King's Music (or Musick, as it was spelled back then). Three years later came another honor, his appointment as the organist to the Chapel Royal. In 1760 Boyce published a collection of his eight symphonies, written during the previous 20 years. A year later he composed music for the wedding of George III to Princess Charlotte, The King Shall Rejoice (here, with the choir of the New College Oxford and the Academy of Ancient Music, Edward Higginbottom conducting). He semi-retired soon after, living in Kensington Gore next to Hyde Park in London and composing occasional pieces. William Boyce died on February 7th of 1779.

September 29, 2014. Recent birthdays. With a lull this week (with one exception: Paul Dukas, of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice fame, was born on October 1st, 1865) we want to go back to some of the anniversaries we failed to properly acknowledge. Among the composers born in September that we mentioned in passing (and there were many), were two whom we’ve never written about before: Johann Christian Bach and William Boyce, both very important composers of the 18th century and both quickly forgotten soon after their death, only to regain popularity later.

Johann Christian Bach, Johann Sebastian’s youngest son, is often called "the London Bach" as he spent the last 20 years of his life in that city. He was born in Leipzig on September 5th, 1735 when his father was already 50. It seems he was Johann Sebastian’s favorite child, as his father left him three of his harpsichords. After Johann Sebastian’s death in 1750 Christian moved to Berlin and continued musical lessons with his older half-brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel. In 1755 Christian left Germany – the first Bach to do so in two centuries – and settled in Milan. He composed and earned his living as the second organist at the Milan Cathedral. His early success came with the opera Catone in Utica, which was staged in many cities around Italy. The King’s Theater, the most important opera company in England, took notice, commissioning two operas, and in 1762 Christian moved to London. He soon became the most important composer in the city, accepted by the royal family, with patrons among the aristocracy and friends like Gainsborough and other painters and artists. He wrote variations on God Save the King into the sixth of his keyboard concertos Op. 1, and it became exceedingly popular. Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, a composer and viol player, organized a series of concerts, an important milestone in London’s music life. In 1764 Leopold Mozart arrived in London with his eight year-old musical prodigy of a son. Young Wolfgang held Johann Christian’s music in highest regard; later he would rework three of his piano sonatas into concertos (here is the original Sonata Op.5 no. 2 performed by the Austrian pianist Hans Kann, and here’s the 15 year-old Mozart’ concerto K. 107 no. 1; Ton Koopman performs with the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra). In London they even played harpsichord duets together. Christian’s symphonic music also influencedMozart’s early work. We’ll write more about Johann Christian some other time, his keyboard concertos and especially his very popular operas. In the mean time, here is his Sinfonia in D major, Op. 18, No. 4; Hanspeter Gmur leads the Failoni Orchestra of Budapest.

left him three of his harpsichords. After Johann Sebastian’s death in 1750 Christian moved to Berlin and continued musical lessons with his older half-brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel. In 1755 Christian left Germany – the first Bach to do so in two centuries – and settled in Milan. He composed and earned his living as the second organist at the Milan Cathedral. His early success came with the opera Catone in Utica, which was staged in many cities around Italy. The King’s Theater, the most important opera company in England, took notice, commissioning two operas, and in 1762 Christian moved to London. He soon became the most important composer in the city, accepted by the royal family, with patrons among the aristocracy and friends like Gainsborough and other painters and artists. He wrote variations on God Save the King into the sixth of his keyboard concertos Op. 1, and it became exceedingly popular. Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, a composer and viol player, organized a series of concerts, an important milestone in London’s music life. In 1764 Leopold Mozart arrived in London with his eight year-old musical prodigy of a son. Young Wolfgang held Johann Christian’s music in highest regard; later he would rework three of his piano sonatas into concertos (here is the original Sonata Op.5 no. 2 performed by the Austrian pianist Hans Kann, and here’s the 15 year-old Mozart’ concerto K. 107 no. 1; Ton Koopman performs with the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra). In London they even played harpsichord duets together. Christian’s symphonic music also influencedMozart’s early work. We’ll write more about Johann Christian some other time, his keyboard concertos and especially his very popular operas. In the mean time, here is his Sinfonia in D major, Op. 18, No. 4; Hanspeter Gmur leads the Failoni Orchestra of Budapest.

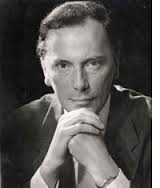

The fine portrait of Johann Christian, above, was painted by Thomas Gainsborough in 1776.Permalink

September 22, 2014. Panufnik, Shostakovich and Rameau. The Polish composer Andrzej Panufnik was born 100 years ago, on September 24th of 1914 in Warsaw. His mother was a violinist, his father – a famous violin-maker. As a young boy Andrzej showed interest in music but his father didn’t approve, so even though he took piano lessons, the studies were erratic. He never learned to play piano well enough and in order to enter the Warsaw Conservatory had to join the department of percussion instruments. He soon dropped the percussions and switched to conducting and composition. His first known work (a trio) dates from 1934. After graduating, he spent some time studying in Vienna, and then went to Paris. In both cities he heard a lot of new music, from Schoenberg to Berg to Bartók. Panufnik returned to Warsaw shortly before the start of the Second World War. Throughout the war he stayed in the city, like his good friend Witold Lutoslawski; to earn some extra money they played piano duos in cafés. After the war Panufnik picked up several conducting positions and soon became highly respected in this field. He also continued composing, and several of his compositions received national recognition and prizes. But things were changing in the now Stalinist Poland. Like so many composers of the eastern block, he was compelled to write “socialist-realist” music, while some of his serious compositions were severely criticized. Still, as a composer of note, he maintained a relatively privileged position, which allowed him to travel abroad to conduct. During one of these trips, while in Zurich in 1954, he escaped to the West. Both his name and his music were immediately banned in Poland, disappearing as if they never existed. He settled in England where life turned out to be rather difficult: after the initial attention his defection had received he was all but forgotten. To earn money he turned to conducting again; in 1957 he was appointed music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He held this post for two years but then quit to continue composing full time. His work was occasionally performed in England and the US, but the big break happened in 1963 when his Sinfonia Sacra won the Prince Rainier Competition. Commissions and recordings followed: Leopold Stokowski, himself of Polish descent and a Panufnik champion of many years, recorded his Universal Prayer; Jascha Horenstein also recorded several pieces. Yehudi Menuhin commissioned him a violin concerto and Seiji Ozawa did the same for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. As Panufnik’s fame grew and the regime in Poland got milder, his name was resurrected in his native country. Some of his compositions returned to the concert stage but Panifnik waited for another 13 years, till after the first democratic government had been elected, before visiting Poland. That was in 1990 and Panufnik had just one year to live. He was productive till the end, performing the premier of his Symphony no. 10 in Chicago that same year and completing the Cello concerto, which he wrote for Mstislav Rostropovich, shortly before his death.

interest in music but his father didn’t approve, so even though he took piano lessons, the studies were erratic. He never learned to play piano well enough and in order to enter the Warsaw Conservatory had to join the department of percussion instruments. He soon dropped the percussions and switched to conducting and composition. His first known work (a trio) dates from 1934. After graduating, he spent some time studying in Vienna, and then went to Paris. In both cities he heard a lot of new music, from Schoenberg to Berg to Bartók. Panufnik returned to Warsaw shortly before the start of the Second World War. Throughout the war he stayed in the city, like his good friend Witold Lutoslawski; to earn some extra money they played piano duos in cafés. After the war Panufnik picked up several conducting positions and soon became highly respected in this field. He also continued composing, and several of his compositions received national recognition and prizes. But things were changing in the now Stalinist Poland. Like so many composers of the eastern block, he was compelled to write “socialist-realist” music, while some of his serious compositions were severely criticized. Still, as a composer of note, he maintained a relatively privileged position, which allowed him to travel abroad to conduct. During one of these trips, while in Zurich in 1954, he escaped to the West. Both his name and his music were immediately banned in Poland, disappearing as if they never existed. He settled in England where life turned out to be rather difficult: after the initial attention his defection had received he was all but forgotten. To earn money he turned to conducting again; in 1957 he was appointed music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He held this post for two years but then quit to continue composing full time. His work was occasionally performed in England and the US, but the big break happened in 1963 when his Sinfonia Sacra won the Prince Rainier Competition. Commissions and recordings followed: Leopold Stokowski, himself of Polish descent and a Panufnik champion of many years, recorded his Universal Prayer; Jascha Horenstein also recorded several pieces. Yehudi Menuhin commissioned him a violin concerto and Seiji Ozawa did the same for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. As Panufnik’s fame grew and the regime in Poland got milder, his name was resurrected in his native country. Some of his compositions returned to the concert stage but Panifnik waited for another 13 years, till after the first democratic government had been elected, before visiting Poland. That was in 1990 and Panufnik had just one year to live. He was productive till the end, performing the premier of his Symphony no. 10 in Chicago that same year and completing the Cello concerto, which he wrote for Mstislav Rostropovich, shortly before his death.

We’ll hear two compositions by Panufnik: first the Nocturne, an early work from 1947 (here, performed by the Louisville Orchestra, Robert Whitney conducting), and Autumn Music, from 1962 (Jascha Horenstein leads the London Philharmonic Orchestra, here).

Another eminent composer of the 20th century, Dmitry Shostakovich, was born on September 25th of 1906. Shostakovich and Panufnik knew each other well: they met during Panufnik’s trips to Russia. And as different as their music is, their lives had many things in common: sporadic political prosecution, banned music, pressure to write in the “patriotic,” “socialist-realism” mode, unfortunate compromises they were forced into. Panufnik managed to escape, the more timid Shostakovich would’ve never even dreamed of it.

Also on September 25th but almost two and a half centuries earlier, in 1683, one of the greatest composer of the French Baroque was born, Jean-Philippe Rameau.Permalink