Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

June 22, 2015. Schumann’s Dichterliebe, Part II. In the absence of any significant birthdays this week we decided to publish the second part of the article on Robert Schumann’s song cycle Dichterliebe (A Poet's Love). The first part was published here. As a reminder, Dichterliebe, o n texts by Heinrich Heine from his Lyrisches Intermezzo, was written in 1840. That was the year Schumann married Clara Wieck; it also turned into his Liederjahr – the year of songs: he wrote almost 140 of them in a tremendous creative spurt. Dichterliebe is probably the best known. To illustrate the cycle, we used recordings made by Fritz Wunderlich. All but the one were made in Salzburg in 1965. The recording of Die alten, bösen Lieder was made during a concert in Usher Hall, Edinburgh, on August 4th of 1966. Wunderlich tragically died just one month later; he was 35 years old. ♫

n texts by Heinrich Heine from his Lyrisches Intermezzo, was written in 1840. That was the year Schumann married Clara Wieck; it also turned into his Liederjahr – the year of songs: he wrote almost 140 of them in a tremendous creative spurt. Dichterliebe is probably the best known. To illustrate the cycle, we used recordings made by Fritz Wunderlich. All but the one were made in Salzburg in 1965. The recording of Die alten, bösen Lieder was made during a concert in Usher Hall, Edinburgh, on August 4th of 1966. Wunderlich tragically died just one month later; he was 35 years old. ♫

The poet’s state becomes even more pitiful in “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen” (“There is fluting and fiddling,” here) as he witnesses the joyous festivities of the marriage of his beloved to another man. He gazes upon the merriment, watching her dance (“Da tanzt wohl den Hochzeitreigen / Die Herzallerliebste mein”) to the sound of flutes, fiddles, shawms, and drums. Betwixt the sounds of the instruments, the angels weep for the lonely poet (“Dazwischen schluchzen und stöhnen / Die guten Engelein”). Schumann’s setting portrays the dance of the beloved and her wedding guests. However, its D minor tonality and chromatic harmonies undoubtedly identify that the listener is viewing the scene through the prism of the poet’s broken heart.

Utter despair sets in the following song, “Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen” (“I hear the dear song sounding,” here). Pained by watching his beloved married to another, the poet now hears the sweet song she once sang, a symbol that her love is forever no longer his. In his desolation, he seeks the solace of nature, wandering deep into the forest to weep. Schumann’s setting is through-composed in the key of G minor. The doleful vocal melody closes first in the key of the subdominant at the conclusion of the first stanza, poignantly affected by a Neapolitan sixth. The second stanza then slowly descends back to the tonic of G minor. Against the vocal melody is an accompaniment of descending arpeggios, which with the song’s slow tempo depict the falling tears of the poet. As with many of Schumann’s song, the climax comes as the vocalist exits. Shadowing the final notes of the melody, the piano begins a heartrending coda which culminates as chromatically ascending harmonies beneath a tonic pedal suddenly break into a descending passage of sixteenth notes through almost three octaves. Here, the listener beholds the poet’s heart bursting with pain (“So will mir die Brust zerspringen / Vor wildem Schmerzendrang”). (Continue reading here)Permalink

June 15, 2015. Stravinsky and more. Several composers were born this week: Edvard Grieg, Norway’s national composer (he was born on June 15th of 1843), the Frenchman Charles Gounod (born on June 17th of 1818), Jacques Offenbach, who was born just a year later, on June 20th of 1819 in Cologne to a Jewish cantor but lived most of his life in Paris and received a Légion d’Honneur from the hands of the Emperor Napoleon III; and Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, the ninth of Johann Sebastian Bach’s children (he was born on June 21st of 1732). To mark these birthdays, we’ll play: Solveig’s song, from Grieg’s original incidental music to Peer Gynt with the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko (here); Gounod’s lovely Serenade, exquisitely performed by Joan Sutherland (with her husband, Richard Bonynge, on the piano, here); a comic aria Les oiseaux dans la charmille from Offenbach’s only opera, The Tales of Hoffmann with another Australian soprano, Emma Matthews (here); and the only non-vocal entry, Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach’s Piano Concerto E Major, with Cyprien Katsaris and Orchestre de Chambre du Festival d`Echternach (here).

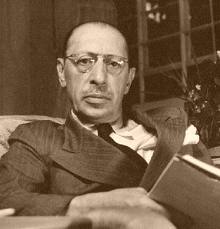

But the most significant composer of them all was, without a doubt, the great Igor Stravinsky. Stravinksy was born on June 17, 1882 in Oranienbaum, outside of Saint Petersburg. During his long life Stravinsky moved from one country to another (after leaving Russia he lived in France, Switzerland and the US); he also didn’t stay still compositionally, often discarding one style, however successful it was for him, and adopting a new musical paradigm. It is hard to imagine that the same composer who wrote The Rite of Spring, with its wild colors and brutal rhythms, would just 15 years later create a ballet as abstract and serene as Apollon musagète, or, for that matter, some years later, another ballet, Agnon, written in the twelve-tone system. Probably the only other person who could reinvent himself as often and with the same immense success was Pablo Picasso. Stravinsky naturally possessed a tremendous technique, which allowed him to imitate or directly quote other composers while maintaining the artistic integrity and originality of the composition. He used this skill with uncanny virtuosity when he wrote the ballet Le Baiser de la Fée (The Fairy's Kiss), an homage to his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky. The ballet was commissioned in 1927 by the famous Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein; Stravinsky completed the ballet in 1928, on the 35th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death (it was premiered in November of that year). The libretto was based on Hans Christian Andersen's story The Ice Maiden. Bronislava Nijinska (Vaclav’s sister) was the choreographer. Stravinsky used several of Tchaikovsky’s piano pieces and songs, and recognizably Tchaikovskian sonorities throughout the ballet. A tremendously inventive piece, it marked another step in the development of Stravinsky’s compositional style. In 1934 he wrote a suite based on the music of the ballet; this suite, which Stravinsky called Divertimento, is usually performed in concerts. We’ll hear it in the performance by the Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mark Kadin conducting.

But the most significant composer of them all was, without a doubt, the great Igor Stravinsky. Stravinksy was born on June 17, 1882 in Oranienbaum, outside of Saint Petersburg. During his long life Stravinsky moved from one country to another (after leaving Russia he lived in France, Switzerland and the US); he also didn’t stay still compositionally, often discarding one style, however successful it was for him, and adopting a new musical paradigm. It is hard to imagine that the same composer who wrote The Rite of Spring, with its wild colors and brutal rhythms, would just 15 years later create a ballet as abstract and serene as Apollon musagète, or, for that matter, some years later, another ballet, Agnon, written in the twelve-tone system. Probably the only other person who could reinvent himself as often and with the same immense success was Pablo Picasso. Stravinsky naturally possessed a tremendous technique, which allowed him to imitate or directly quote other composers while maintaining the artistic integrity and originality of the composition. He used this skill with uncanny virtuosity when he wrote the ballet Le Baiser de la Fée (The Fairy's Kiss), an homage to his favorite composer, Tchaikovsky. The ballet was commissioned in 1927 by the famous Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein; Stravinsky completed the ballet in 1928, on the 35th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death (it was premiered in November of that year). The libretto was based on Hans Christian Andersen's story The Ice Maiden. Bronislava Nijinska (Vaclav’s sister) was the choreographer. Stravinsky used several of Tchaikovsky’s piano pieces and songs, and recognizably Tchaikovskian sonorities throughout the ballet. A tremendously inventive piece, it marked another step in the development of Stravinsky’s compositional style. In 1934 he wrote a suite based on the music of the ballet; this suite, which Stravinsky called Divertimento, is usually performed in concerts. We’ll hear it in the performance by the Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mark Kadin conducting.

PermalinkJune 8, 2015. Schumann’s Dichterliebe. The great German composer Robert Schumann was born on this day in 1810. We write about him every year (for example, here and here in the past couple of years), so this time we’ll do something different: publish an article on the first eight songs of Dichterliebe. Schumann wrote more than 300 songs, but A Poet’s Love cycle contains some of his greatest. There are so many wonderful recordings of Dichterliebe that it was difficult to decide which one to use to illustrate the cycle. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau alone made four different recordings, two of them with remarkable pianists: Alfred Brendel in 1985 and, live, with Vladimir Horowitz, in 1976. Gérard Souzay, a wonderful French baritone, also recorded it several times, once with Afred Cortot (and there’s another recording with Cortot, in which he accompanies Charles Panzéra). Hermann Prey made a tremendous recording, and so did the great German soprano Lotte Lehmann. Out of all of these and many more, we decided on Fritz Wunderlich – the beauty of his crystalline voice, his perfect diction, the natural, unpretentious manner devoid of any affectations make his interpretation, in our opinion, extraordinary. The recording was made live on August 19th of 1965 during the Salzburg Festival. Hubert Giesen was at the piano. ♫

years), so this time we’ll do something different: publish an article on the first eight songs of Dichterliebe. Schumann wrote more than 300 songs, but A Poet’s Love cycle contains some of his greatest. There are so many wonderful recordings of Dichterliebe that it was difficult to decide which one to use to illustrate the cycle. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau alone made four different recordings, two of them with remarkable pianists: Alfred Brendel in 1985 and, live, with Vladimir Horowitz, in 1976. Gérard Souzay, a wonderful French baritone, also recorded it several times, once with Afred Cortot (and there’s another recording with Cortot, in which he accompanies Charles Panzéra). Hermann Prey made a tremendous recording, and so did the great German soprano Lotte Lehmann. Out of all of these and many more, we decided on Fritz Wunderlich – the beauty of his crystalline voice, his perfect diction, the natural, unpretentious manner devoid of any affectations make his interpretation, in our opinion, extraordinary. The recording was made live on August 19th of 1965 during the Salzburg Festival. Hubert Giesen was at the piano. ♫

Schumann’s composed almost exclusively for his own instrument, the piano, during his early years as a composer. The 1830s saw the creation of some of his most well-known compositions, including Papillons, Kinderszenen, and the Fantasie in C. However, in 1840, with virtually no warning, Schumann composed no less than 138 songs. This remarkable creative outpouring has since become known as his “Liederjahr,” or “Year of Song.” Yet, this sudden change, nor the abundance of music written, was purely coincidental. Instead, it makes the culmination of his courtship of Clara Wieck, and their long-awaited and hard-won marriage.

Schumann and Clara first met in March 1828 at a musical evening in the home of Dr. Ernst Carus. Schumann was so impressed with Clara’s skill at the piano that he soon after began piano lessons with her father, Friedrich. During this time he lived in the Wieck’s household, and he and Clara quickly formed a close friendship. With time, their friendship blossomed into a romantic, although clandestine, relationship. On Clara’s 18th birthday, Schumann proposed to her, and she accepted. Friedrich, on the other hand, had less than a favorable opinion of Schumann, and refused to grant permission for Schumann to marry his daughter. This placed a great strain on their relationship, yet they remained devoted to each other by exchanging love letters and meeting in secret. For a moment’s glance of Clara as she left one of her concerts, Schumann would wait for hours in a café. The couple eventually sued Friedrich, and after a lengthy court battle, Clara was finally allowed to marry Schumann without her father’s consent. The wedding took place in 1840. (Continue reading here).Permalink

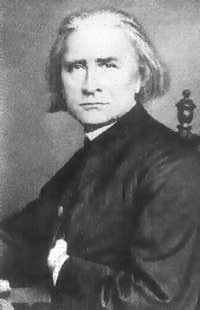

June 1, 2015. Années de Pèlerinage: Troisième Année. In the last several months we published short articles about the first two volumes of Franz Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage: Year One, Switzerland (Première année: Suisse), here, and Year Two, Italy (Deuxième année: Italie) here. Today we’ll continue with the third year, (Troisième année). Probably not as popular, or at least not as often performed as the first two sections, it demonstrates the depth and unparalleled sonorities of Liszt’s late works. We will illustrate each of the seven pieces with performances by Aldo Ciccolini, recorded in 1961. Ciccolini died exactly four months ago, on February 1st, 2015; he was 89. Ciccolini, who was born in Naples into a titled family, became a French citizen in 1969. His was a famous interpreter of the music of his adopted country – Debussy, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, and especially Satie, but he also recorded all piano sonatas of Beethoven, music of Albeniz, Chopin, Bach, Scarlatti, – more than 50 LPs and CDs altogether. A brilliant virtuoso, he was a powerful but sensitive interpreter of Liszt’s music. For many years Ciccolini taught at the Paris Conservatory (Jean-Yves Thibaudet was a pupil). His last recording, featuring piano sonatas by Mozart and Muzio Clementi, was made when Ciccolini was 85. (The photo portrait of Liszt, above, was made in 1867). ♫

année: Italie) here. Today we’ll continue with the third year, (Troisième année). Probably not as popular, or at least not as often performed as the first two sections, it demonstrates the depth and unparalleled sonorities of Liszt’s late works. We will illustrate each of the seven pieces with performances by Aldo Ciccolini, recorded in 1961. Ciccolini died exactly four months ago, on February 1st, 2015; he was 89. Ciccolini, who was born in Naples into a titled family, became a French citizen in 1969. His was a famous interpreter of the music of his adopted country – Debussy, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, and especially Satie, but he also recorded all piano sonatas of Beethoven, music of Albeniz, Chopin, Bach, Scarlatti, – more than 50 LPs and CDs altogether. A brilliant virtuoso, he was a powerful but sensitive interpreter of Liszt’s music. For many years Ciccolini taught at the Paris Conservatory (Jean-Yves Thibaudet was a pupil). His last recording, featuring piano sonatas by Mozart and Muzio Clementi, was made when Ciccolini was 85. (The photo portrait of Liszt, above, was made in 1867). ♫

Années de Pèlerinage: Troisième Année

In 1883, three years before Liszt’s death, the third and final volume of Années de Pèlerinage was published. Unlike it companions, which were musical travelogues of Liszt’s journeys throughout Switzerland and Italy, the third volume bore no subtitle to reveal the source of its inspiration (though four of its pieces still drew their inspiration from landmarks in Italy). Instead, Troisième Année is strikingly different from the previous two volumes. While still remaining technically challenging, many of the pieces are far removed from the virtuosic showpieces Liszt produced in his youth. These pieces were intensely personal creations. Liszt was certainly aware of this fact, and even warned his publisher not to expect this third volume to be as commercially successful as its predecessors. On the whole, Liszt was correct and Troisième Année failed to impress audiences. Today, along with the rest of Années de pèlerinage, it is considered one of Liszt’s masterpieces. (Continue reading here)Permalink

May 25, 2015. Chopin’s Waltzes. With apologies to the devotees of the music of Isaac Albéniz, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Marin Marais, all of whom were born this week, we’re publishing a longer piece by Joseph DuBose on waltzes by Frédéric Chopin. We’ll illustrate each of these concise gems with performances, some by the young artists for whom Classical Connect serves as a virtual concert stage: Bill-John Newbrough, Anastasya Terenkova, Konstantyn Travinsky, Yury Shadrin; others – by the acknowledged masters. You’ll hear the 77 year-old Artur Rubinstein live in Moscow (you can hear him announcing the encore), Evgeny Kissin live in Carnegie Hall, Zoltan Kocsis, Philippe Entremont, the French pianist and conductor, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Dinu Lipatti in a recording made in 1950, just months before his death at the age of 33; Vladimir Ashkenazy and Samson François in a 1963 recording. ♫

for whom Classical Connect serves as a virtual concert stage: Bill-John Newbrough, Anastasya Terenkova, Konstantyn Travinsky, Yury Shadrin; others – by the acknowledged masters. You’ll hear the 77 year-old Artur Rubinstein live in Moscow (you can hear him announcing the encore), Evgeny Kissin live in Carnegie Hall, Zoltan Kocsis, Philippe Entremont, the French pianist and conductor, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Dinu Lipatti in a recording made in 1950, just months before his death at the age of 33; Vladimir Ashkenazy and Samson François in a 1963 recording. ♫

The waltz is inextricably connected to that great musical city of Vienna. Thus, when, as a budding composer and pianist, Frederic Chopin made his debut in the city in 1829 soon after his graduation from the Warsaw Conservatory, and again visited in 1830, it is no surprise that he tried to assimilate himself into its musical culture by performing and even composing waltzes. Yet, Chopin’s Polish roots ran too deep, and he was never able to fully master the distinctive waltz style. On his return from the Austrian capital, he admitted to a friend, “I have acquired nothing of that which is specially Viennese by nature, and accordingly I am still unable to play valses.”

Chopin’s earliest waltzes roughly date from the time of his first visit to Vienna. Yet, these early attempts remained unpublished during the composer’s lifetime. Indeed, his first waltz only appeared in print after he had left Vienna for Paris, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Currently, there are eighteen known waltzes that Chopin composed, though it is believed he wrote others. However, only the first fourteen are generally numbered. Of these fourteen, only eight were published during Chopin’s lifetime—opp. 18 and 42, and the two sets of three of opp. 34 and 64. Five more were issued in the decade following Chopin’s death and make up opp. 69 and 70. Finally, two others appeared during the remainder of the 19th century—the well-known E minor waltz in 1868 and another in E major in the early 1870s. (Continue reading here).

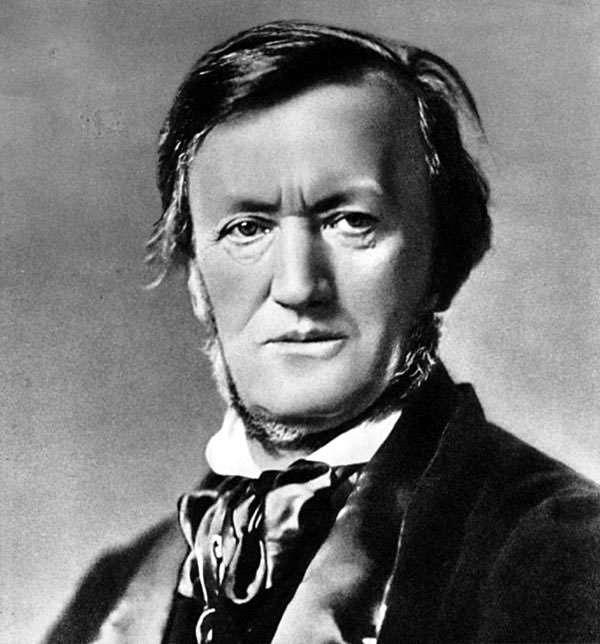

PermalinkMay 18, 2015. Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd of 1813. Somehow, this date seems incongruous: was he really just three years younger than Chopin and Schumann? Those are geniuses firmly established in the Pantheon of classical music, while people still argue about Wagner. His music and his writings still can create controversies, as we’ll see in a minute. Wagner was living in Paris when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

when he completed his third and fourth operas, Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman. He approached Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German-Jewish composer who was living in Paris and asked for advice on the staging of Rienzi. Wagner’s letters to Meyerbeer sound almost obsequious, which is worth noticing, considering the events that followed. In the previous decade Meyerbeer had conquered Paris with his own operas, Robert le Diable in particular. Even though he had lived in Paris for many years, Meyerbeer still maintained connections in Germany, which he used to help Wagner, in Dresden with Rienzi and in Berlin with The Flying Dutchman. In 1842 Rienzi was accepted at the Dresden Court Theater and Wagner moved there right away. The opera was premiered in October of that year and proved to be a success, Wagner’s first. A couple years later he was appointed the conductor at the Court Theater. Wagner, whom Meyerbeer not only helped at a critical moment of Wagner’s life, but who also deeply influenced him by his operas, eventually became Meyerbeer’s biggest enemy. He wrote several pamphlets against Meyerbeer, all of them deeply anti-Semitic in nature. But that was to come later. While still in Dresden, Wagner wrote Tannhäuser, an opera on his own libretto, derived from German legends about a 13th-century German minnesinger Henrich Tannhäuser and a certain song contest. Long, convoluted, and at times incoherent, it tells a story of the poet and singer Tannhäuser who lives in the realm of Venus, the goddess of love, surrounded by young beautiful women. After some sexual shenanigans he decides that he’s had enough and returns to real life in Wartburg. There, the local count holds a song contest. Tannhäuser’s love song is considered too profane and he’s banished from Wartburg and ordered to visit the Pope. More fantastic events take place, involving Tannhäuser, his love interest Elisabeth, and his friend Wolfram, with Venus making an appearance and the Pope’s staff flowering at the very end of the opera. None of it makes much sense, but the juxtaposition of Venus and the church, of lust, love and faith gives directors ample opportunity to excersize their fantazy. Modern productions set Tannhäuser in different eras and some use a good doze of nudity and profanity. One such production, rather mild by European standards, was recently created in the Russian city of Novosibirsk. What followed was a rather typical Russian story. The hierarchs of the local Orthodox church rose in protest, and so did the more conservative members of the local society. Demonstrations were staged, accusations were hurled in the media, the courts got involved. And even though some members of the Russian artistic community tried (rather meekly, it has to be said) to defend the production, the minister of culture moved in and sacked the director. Truly, modern Russia is more bizarre than any of Wagner’s librettos.

All of this doesn’t really matter: the music of Tannhäuser is great, and gets better as the opera evolves. The third act is magnificent. Here’s an excerpt, with the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the orchestra of Staatsoper Berlin, Franz Konwitschny conducting.

Permalink