Welcome to our free classical music site

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

Do you write about classical music? Are you a blogger? Want to team up with Classical Connect? Send us a message, let's talk!

March 25, 2019. Composers, performers… This is another overabundant week. Franz Joseph Haydn was born on March 31st of 1732. And one of the most important composers of the first half of the 20th century, Béla Bartók, was born on this day, March 25th of 1881. The second half of the last century is also represented, by none other than Pierre Boulez, born on March 26th of 1925. And then there are two composers from previous eras: the 18th century Johann Adolph Hasse, born 320 years ago, on March 25th of 1699, whose opere serie were, for a while, some of the most popular in all of Europe – that, given that among his competitors were the young Handel and still very active Italians of the older generation, from Alessandro Scarlatti to Petri, Bononcini, Caldara, and Porpora. And from two centuries earlier, one of the most important composers of the Spanish Renaissance, Antonio de Cabezón, who was born on March 30th of 1510. (We’ve written about all them several times, for example here, here, here, and here).

And then there are two eminent pianists, Wilhelm Backhaus and Rudolf Serkin. Backhaus was born on March 26th of 1884 in Leipzig, Serkin – on March 28th of 1903 in Eger, a town in Bohemia now called Cheb. Both immensely talented, both great interpreters of the music of Beethoven, both native German speakers, both spent a lot of time in the US, but it’s hard to imagine more different biographies. Backhaus was close to the Nazis and knew Hitler personally, though eventually he emigrated from Nazi Germany to Switzerland. Serkin, of Russian-Jewish decent, lived in Vienna and then in Berlin, but after the rise of Nazism had to flee Germany first to Switzerland then to the US. We’ll write about both and compare some of their recordings.

That’s not all: Mstislav Rostropovich, one of the greatest cellists of the 20th century, was also born this week – on March 27th of 1927, in Baku, the capital of now-independent Azerbaijan. Not just a phenomenal cellist, he was also a conductor and, at the time when all civic activity was suppressed, an active supporter of the banned writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. For that the Soviets punished Rostropovich, canceling all his foreign tours. In 1974, thanks to Senator Edward Kennedy and active Western public opinion, Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, were allowed to leave the Soviet Union; they returned only after the fall of the Communist regime in 1991. Rostropovich is another brilliant musician on our “to do” list. And as if that wasn’t enough, Arturo Toscanini, who needs no introduction, was born on this day in 1867 in Parma.

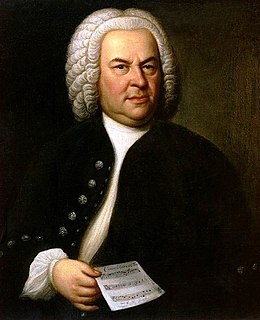

March 18, 2019. Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21st of 1685. Last year, while celebrating his birthday, we focused on the period of mid-1730s, when Bach was living in Leipzig and was involved with Collegium Musicum, an association of professional musicians and students, which was created by Telemann in 1702 for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During Bach’s tenure, the summer concerts took place on Wednesdays between 4 and 6 p.m. in the coffee-garden “near the Grimmisches Thor (gates)”; during the winter time – on Fridays between 8 and 10 p.m. in Zimmermann’s coffee-house. Many of Bach’s works were performed during these concerts, some old and some new. The famous Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052 was one of them, and so were the other six concertos, BWV 1053 through BWV 1058. Also performed were his orchestral suites, violin concertos and other pieces. He played the music of other composers as well, and, according to his son, C.P.E. Bach, all famous musicians passing through Leipzig played for him.

students, which was created by Telemann in 1702 for the purpose of producing regular public concerts. During Bach’s tenure, the summer concerts took place on Wednesdays between 4 and 6 p.m. in the coffee-garden “near the Grimmisches Thor (gates)”; during the winter time – on Fridays between 8 and 10 p.m. in Zimmermann’s coffee-house. Many of Bach’s works were performed during these concerts, some old and some new. The famous Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052 was one of them, and so were the other six concertos, BWV 1053 through BWV 1058. Also performed were his orchestral suites, violin concertos and other pieces. He played the music of other composers as well, and, according to his son, C.P.E. Bach, all famous musicians passing through Leipzig played for him.

Going back to the harpsichord concertos: while they sound original, most of their music had been written by Bach earlier. For example, here is the first movement of the Harpsichord Concerto no. 1, BWV 1052, the recording made live by Glenn Gould in 1957 in Leningrad during his historic tour of the Soviet Union (the Leningrad Academic Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Ladislav Slovák). And here is the first movement, Sinfonia, of Bach’s Cantata BWV 146, Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal (We must [pass] through great sadness), composed either in 1726 or 1728. As you can hear, it’s the same music but arranged for a slightly different orchestra, with the keyboard being the organ rather than the harpsichord. The very dynamic organist in the Sinfonia is Howard Moody, the British composer and keyboard player. John Eliot Gardiner conducts the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. The second movement of the concerto was taken from the second movement of the same BWV 146 cantata, except that in this case Bach had to work harder, as converting a choral line to keyboard was not such a straightforward task. Here’s movement II, Adagio, from the concerto, and here – the second movement from the Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal cantata. The third movement of the concerto was also taken from an earlier-written cantata, but in this case, from the first movement of the cantata BWV 188, Ich habe meine Zuversicht (I have [placed] my confidence). Here’s the final movement of the Concerto, and here – the first movement of the Cantata Ich habe meine Zuversicht. We should be grateful to Bach for so brilliantly recycling the old material; he couldn’t have expected that in the 20th century his keyboard concertos would become so popular, and of course he could’ve never predicted the phenomenon of Glenn Gould, but whether fair or not, his concertos are played and recorded much more often than the cantatas.

If you wish to listen to the complete pieces, you could do so by searching our library, or clicking here for the Harpsichord Concerto no. 1, BWV 1052, here – for the Cantata BWV 146, Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal, and here – for the Cantata BWN 188, Ich habe meine Zuversicht.

Nikolai Rinsky-Korsakov, Modest Mussorgsky, and Franz Schreker, an interesting but almost forgotten Austrian composer active at the end of the 19th – first third of the 20th century were also born this week. We’ll get to them another time.Permalink

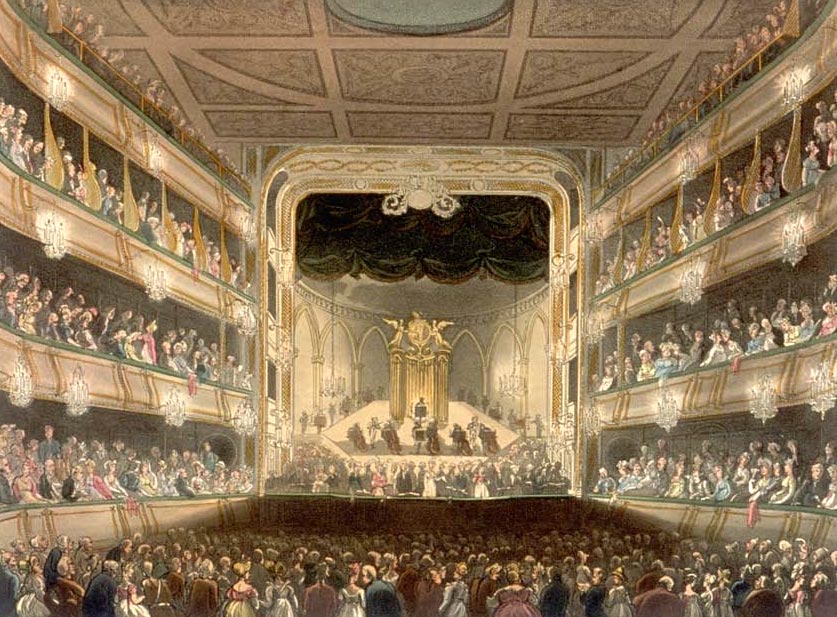

March 11, 2019. Ariodante and Telemann. Just two weeks ago we celebrated Handel’s birthday, and a couple days ago we had a chance to listen to (and, unfortunately, watch) his masterpiece, the opera Ariodante, presented by the Lyric Opera of Chicago. At about 3 hours of pure music (four hours with intermissions) it’s a bit long, but it was written when the public didn’t consider an opera performance a semi-religious event to be experienced in motionless silence – this attitude was acquired a century later – and mingled, talked, played cards and enjoyed themselves as much as they could. Were Handel to write it today, he’d probably cut about a quarter of it out, but even as is, with too many repeats, the music is absolutely gorgeous. The libretto is absurd, but most of the operas then (and since then) had silly storylines.. The characters, all with Italian names and singing in Italian, are placed somewhere in Scotland where two lovers, a prince and king’s daughter, are almost driven to death and madness by a villainous duke, but of course everything ends well: the duke is punished, and the lover happily marry. The premier took place at the Covent Garden; it was the first opera ever staged in the newly-built theater. The role of protagonist, prince Ariodante, was sung by the famous castrato Carestini, who replaced Senesino, for many years Handel’s favorite, after they parted ways and Senesino joined the competing Opera of the Nobility. The bad Duke Polinesso was sung by a contralto, Maria Caterina Negri. At the Lyric, the genders were reversed: Ariodante was sung by a mezzo, while Polinesso – by a countertenor. Both were wonderful. Alice Coote, a prominent interpreter of Handel’s music, needed some time to warm up, but her famous Act II aria, Scherza infida, was superb (here it is in the performance by the countertenor David Daniels, which probably sounds closer to what Handel had in mind). Iestyn Davies was wonderful as Polinesso: his voice is not very big, but it is very focused, projects well and has a remarkable agility. The rest of the cast was excellent.

pure music (four hours with intermissions) it’s a bit long, but it was written when the public didn’t consider an opera performance a semi-religious event to be experienced in motionless silence – this attitude was acquired a century later – and mingled, talked, played cards and enjoyed themselves as much as they could. Were Handel to write it today, he’d probably cut about a quarter of it out, but even as is, with too many repeats, the music is absolutely gorgeous. The libretto is absurd, but most of the operas then (and since then) had silly storylines.. The characters, all with Italian names and singing in Italian, are placed somewhere in Scotland where two lovers, a prince and king’s daughter, are almost driven to death and madness by a villainous duke, but of course everything ends well: the duke is punished, and the lover happily marry. The premier took place at the Covent Garden; it was the first opera ever staged in the newly-built theater. The role of protagonist, prince Ariodante, was sung by the famous castrato Carestini, who replaced Senesino, for many years Handel’s favorite, after they parted ways and Senesino joined the competing Opera of the Nobility. The bad Duke Polinesso was sung by a contralto, Maria Caterina Negri. At the Lyric, the genders were reversed: Ariodante was sung by a mezzo, while Polinesso – by a countertenor. Both were wonderful. Alice Coote, a prominent interpreter of Handel’s music, needed some time to warm up, but her famous Act II aria, Scherza infida, was superb (here it is in the performance by the countertenor David Daniels, which probably sounds closer to what Handel had in mind). Iestyn Davies was wonderful as Polinesso: his voice is not very big, but it is very focused, projects well and has a remarkable agility. The rest of the cast was excellent.

Unfortunately, the production, shared by the Lyric with the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, the Canadian Opera Company, and Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam, was unattractive, silly and in parts, offensive. Placed into a religion-obsessed 1960s Scottish village, it turns the story into a morality play with Polinesso as a rapist-priest and Ginerva, the princess, a victim who rebels, quite awkwardly, at the very end of the opera. Visually boring, its only interesting feature was skillful puppetry which replaced Handel’s ballet numbers. In the absurd finale, while Handel’s glorious music celebrates the marriage of Ariodante and Ginerva, the princess slips away unnoticed and hitches a ride, presumably into a better future. But in the end, this production was just an unfortunate distraction from an otherwise hugely rewarding musical experience.

Georg Philipp Telemann was born on March 14th of 1681. Four years older than Handel (and Bach), he was friends with both. Telemann first met Handel in Halle in 1701 (Handel was only 16 but had already composed several Church cantatas, now lost). In his later years Telemann took up gardening, then in vogue, and received exotic plants from Handel. While in Hamburg, Telemann conducted several of Handel’s operas and even wrote additional music for some of them. And, like Handel, he wrote a piece called Water Music. Not as famous as Handel’s, it still is a marvelous piece. Here it’s performed by the Zefiro Baroque Orchestra.Permalink

March 4, 2019. Plethora. Nine composers and a conductor were born this week. The farthest removed from us, but still sounding unorthodox and fresh is Carlo Gesualdo, a great composer, a nobleman and a murderer. Prince of Venosa, he was born in that southern Italian city on March 8th of 1566 (you can read more about this fascinating person here). His music is quite remarkable in its use of chromaticism, as you can hear in this recording of Itene, o miei sospiri, a madrigal from Book V, published in 1611. It’s performed by the Italian ensemble Delitiae Musicae under the direction of Marco Longhini.

nobleman and a murderer. Prince of Venosa, he was born in that southern Italian city on March 8th of 1566 (you can read more about this fascinating person here). His music is quite remarkable in its use of chromaticism, as you can hear in this recording of Itene, o miei sospiri, a madrigal from Book V, published in 1611. It’s performed by the Italian ensemble Delitiae Musicae under the direction of Marco Longhini.

Antonio Vivaldi was born more than 100 years later, on March 4th of 1678. While Gesualdo’s music bridges the late Renaissance with the early Baroque, Vivaldi was writing when the Italian Baroque was at its peak. We know him best for his concertos (the Four Seasons being by far the most popular), but he also wrote church music, as, for example, this Canta in prato, from Introduzione al Dixit. The Scottish soprano Margaret Marshall and the English Chamber Orchestra are conducted by Vittorio Negri.

In addition to the two above, five more composers were born in Europe: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach on March 8th of 1714, Josef Mysliveček – on March 9th of 1737, Pablo de Sarasate – on March 10th of 1844, Maurice Ravel – on March 7th of 1875, and Arthur Honegger – on March 10th of 1892. CPE Bach and Mysliveček were fine representatives of the early Classical period; Sarasate was a Romantic, Ravel – an Impressionist, and Honegger – a member of Les Six, who were both influenced by and rejected Impressionism. By the end of the 19th century European classical music tradition spread over the American continents, and two of our composers were born there: Heitor Villa-Lobos, in Brazil, on March 5th of 1887, and Samuel Barber, in the US, on March 9th of 1910.

From Gesualdo to Barber – that’s a wonderful arc, and we could play hours of great music by these composers, but we’d like to celebrate a different milestone: Bernard Haitink will turn 90 today, March 4th. We had the pleasure of hearing him conduct the Chicago Symphony on many occasions; his interpretations of Mahler are superb, only Pierre Boulez (whose approach was very differen) could reach the same level of musicianship with his award-winning version of the Ninth Symphony. Haitink was born in Amsterdam. As a child he studied the violin; he joined the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra as a violinist. Soon after he started conducting with that orchestra and at the age of 27 became its principal conductor. In 1956 he got a chance to conduct the great Concertgebouw Orchestra, when Carlo Maria Giulini became indisposed and Haitink was asked to step in (Cherubini's Requiem was in the program). The concert went very well and soon Haitink was made a guest conductor. In 1961 he became Concertgebouw’s youngest ever principal conductor, a position he shared for two years with the famous German, Eugen Jochum; in 1963 Jochum left and Haitink remained as the only principal conductor. While at the Concertgebouw, in 1967, he became involved with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (there, he was also the principal conductor); he worked and toured with both. Haitink was a prolific opera conductor: in 1977 he became the musical director of the Glyndebourne Festival; he also worked at the Metropolitan Opera and the Covent Garden. With the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, he video-recorded the full Ring cycle. In 2006 Haitink was made the principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony and later was offered the position of the music director but declined citing his age. Here’s the Finale, of Mahler’s Symphony no. 6 (Allegro moderato - Allegro energico). The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is conducted by Bernard Haitink.Permalink

February 25, 2019. Chopin. Frédéric Chopin was born on March 1st of 1810. Here’s a brief sketch of Chopin’s first 20 years. He was born in Żelazowa Wola, not far from Warsaw, in what then was the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw, created by Napoleon three years earlier (the Duchy would disappear five years later, following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, with that part of Poland reverting back to Russia). His father, Nicolas Chopin, was French, his mother, Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska, – Polish. The first 20 years Frédéric lived in Poland, mostly in Warsaw, where his family moved when Nicolas received an appointment at the newly-established Warsaw Lyceum. Frédéric was a child prodigy (“Second Mozart,” the local press called him), both as a pianist and as a composer: a lithograph of a polonaise he wrote at the age of eight, survives to this day. He studied composition and the piano with the composer Józef Elsner, then entered the Warsaw Conservatory, where he also studied the organ. The organ played its role, even though Chopin never composed for this instrument: at the time, several attempts were made to combine the organ and the piano; one of these hybrids was called the “aeolopantaleon.” Young Chopin played this unusual instrument at a concert attended by Tsar Alexander I of Russia; the Tsar was very impressed and presented the 15-year-old Frédéric with a diamond ring. Even though the Chopins were well established, Frédéric felt stifled: compared to the European capitals or St.Petersburg, Warsaw was musically quite provincial. In November of 1830 he went on a European tour; the first stop was in Vienna. One week after his arrival he had learned of the Warsaw uprising against the Russians. Frédéric stayed in Vienna for half a year; in July of 1831 he left for Paris which would become his home for the rest of his life: he was never to see Poland again. By then, Chopin’s reputation as a brilliant pianist had been firmly established, but his creative genius was to flourish in France.

would disappear five years later, following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, with that part of Poland reverting back to Russia). His father, Nicolas Chopin, was French, his mother, Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska, – Polish. The first 20 years Frédéric lived in Poland, mostly in Warsaw, where his family moved when Nicolas received an appointment at the newly-established Warsaw Lyceum. Frédéric was a child prodigy (“Second Mozart,” the local press called him), both as a pianist and as a composer: a lithograph of a polonaise he wrote at the age of eight, survives to this day. He studied composition and the piano with the composer Józef Elsner, then entered the Warsaw Conservatory, where he also studied the organ. The organ played its role, even though Chopin never composed for this instrument: at the time, several attempts were made to combine the organ and the piano; one of these hybrids was called the “aeolopantaleon.” Young Chopin played this unusual instrument at a concert attended by Tsar Alexander I of Russia; the Tsar was very impressed and presented the 15-year-old Frédéric with a diamond ring. Even though the Chopins were well established, Frédéric felt stifled: compared to the European capitals or St.Petersburg, Warsaw was musically quite provincial. In November of 1830 he went on a European tour; the first stop was in Vienna. One week after his arrival he had learned of the Warsaw uprising against the Russians. Frédéric stayed in Vienna for half a year; in July of 1831 he left for Paris which would become his home for the rest of his life: he was never to see Poland again. By then, Chopin’s reputation as a brilliant pianist had been firmly established, but his creative genius was to flourish in France.

Two prominent 20th century pianists were born this week; both (obviously) played Chopin. Dame Myra Hess was born (likely) in London on this day in 1890. Already prominent as a keen interpreter of the music of Bach, Beethoven and Mozart, she became famous for establishing lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery during the War. Concerts took place Monday through Friday, no matter what. When London was being bombed by the Germans, the concerts were moved to a different, more secure, room. Almost 2000 concerts were presented, and Myra Hess played 150 of them. The Chicago-based free Dame Myra Hess concerts, which take place every Wednesday at 12:15 every week of the year, where established by the International Music Foundation in honor of that great British pianist. Here’s Myra Hess playing The Grande valse brillante in E-flat major, Op. 18.

Lazar Berman was born on February 26th of 1930 into a Jewish family in Leningrad. A child prodigy, he started playing piano at the age of two, and at four took part in a Leningrad “young talents” competition. Later, he studied with Alexander Goldenweiser at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1956 Berman won the Queen Elizabeth competition in Brussels and the Franz Liszt competition in Budapest. Berman was persecuted by the Soviet musical authorities more than almost any artist: from 1959 till 1971 he was prohibited from playing outside of the country because he married a French girl (the marriage was very brief), and then, in 1980, he was banned again, when a “wrong” book was found in his luggage. Berman was a phenomenal virtuoso (his Liszt recordings are stupendous), but partly for that reason the purely musical qualities of his playing were overlooked. Here is Chopin’s Etude in A minor, Op 25, No. 11 in a live recording made in 1950.Permalink

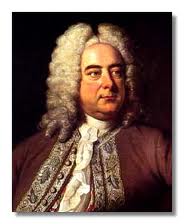

February 18, 2019. Handel. February 23rd is the birthday of George Frideric Handel, one of the greatest composers of the first half of the 18th century. A couple years ago we posted an entry describing Handel’s move to London and his first years there, covering the period roughly between 1709 and 1719. In 1719 Handel was living in Cannons, a home of James Brydges, the Duke of Chandos, about 13 miles northwest of London’s center. The Duke, Handel’s patron, was a musician himself and maintained an orchestra of 24 players. Handel’s stay at Cannons was comfortable and productive: he composed, among other things, Chandos Anthems (eleven in total), and the first English oratorio, Esther. (Here is Chandos Anthem no. 11, "Let God Arise." It’s performed by The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers). In 1719 an opera company, called “Royal Academy of Music” was organized. The Academy was set up as a joint stock company; the original issue was oversubscribed, so many people wanted to get involved. The funding partners were members of the nobility, well-traveled and familiar with opera, often amateur musicians themselves. Their goal was to create a permanent home for Italian opera in London. Handel was tasked with finding the singers, for which he traveled to Germany rather than Italy, but the singers he engaged for the Academy were all Italians, the famous castrato Senesino among them. Upon returning to London Handel was appointed “Master of the Orchester with a Sallary.” The first opera season was short, though Handel produced a new opera, Radamisto; it premiered in April of 1720, the performance attended by King George I and the Prince of Wales, the future George II. Originally the role of Radamisto was sung by a soprano, but during the next season, in a revised version, it was Senestino in his first year in London. That season saw the premier of Handel’s Floridante, very successful and revived in the following seasons. Again, Senesino sung the title role. It’s interesting that the singers were considered much more important than composers and commanded much higher salaries (Senesino’s salary the first year at the Academy was above £2000, an enormous sum). Handel was known to quarrel with the singers often, even with his favorite Senesino: eventually they broke up and Senesino joined the rival Opera of the Nobility. The first couple of seasons Handel’s standing was not as secure as it would seem, considering his position of music director: Giovanni Bononcini, an Italian composer, was a rival, maybe even more famous these first years. The following years saw the ascendancy of Handel at Bononcini’s expense. For the fourth season Handel wrote Ottone, which again featured Senesino in the title role, and also the famous Italian soprano Francesca Cuzzoni as Teofane, Ottone’s future wife. She would sing at the Academy for five more seasons, creating, among others, the role of Cleopatra in Giulio Cesare. (Here’s the aria Vieni, o figlio from Ottone, sung by Lorraine Hunt. Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra is conducted by Nicholas McGegan). The Royal Academy of Music lasted for nine years, through the 1728-29 season, collapsing under the weight of huge salaries paid to the lead singers. It reconstituted itself as New Academy a year later. During those years Handel created 13 operas; Giulio Cesare, being the most famous, but also such masterpieces as Rodelinda and Tamerlano. He also wrote several anthems for the coronation of George II (George I died unexpectedly on June 22nd of 1727), one of which, Zadok the Priest, has been sung at every coronation ceremony since that time. Handel became a British citizen in February of 1727; even before that he was made Composer of Music for His Majesty’s Chapel Royal and taught music to royal princesses. Even though the Academy was no more, things were looking good. Handel was famous, well to do, and only 44.Permalink

describing Handel’s move to London and his first years there, covering the period roughly between 1709 and 1719. In 1719 Handel was living in Cannons, a home of James Brydges, the Duke of Chandos, about 13 miles northwest of London’s center. The Duke, Handel’s patron, was a musician himself and maintained an orchestra of 24 players. Handel’s stay at Cannons was comfortable and productive: he composed, among other things, Chandos Anthems (eleven in total), and the first English oratorio, Esther. (Here is Chandos Anthem no. 11, "Let God Arise." It’s performed by The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers). In 1719 an opera company, called “Royal Academy of Music” was organized. The Academy was set up as a joint stock company; the original issue was oversubscribed, so many people wanted to get involved. The funding partners were members of the nobility, well-traveled and familiar with opera, often amateur musicians themselves. Their goal was to create a permanent home for Italian opera in London. Handel was tasked with finding the singers, for which he traveled to Germany rather than Italy, but the singers he engaged for the Academy were all Italians, the famous castrato Senesino among them. Upon returning to London Handel was appointed “Master of the Orchester with a Sallary.” The first opera season was short, though Handel produced a new opera, Radamisto; it premiered in April of 1720, the performance attended by King George I and the Prince of Wales, the future George II. Originally the role of Radamisto was sung by a soprano, but during the next season, in a revised version, it was Senestino in his first year in London. That season saw the premier of Handel’s Floridante, very successful and revived in the following seasons. Again, Senesino sung the title role. It’s interesting that the singers were considered much more important than composers and commanded much higher salaries (Senesino’s salary the first year at the Academy was above £2000, an enormous sum). Handel was known to quarrel with the singers often, even with his favorite Senesino: eventually they broke up and Senesino joined the rival Opera of the Nobility. The first couple of seasons Handel’s standing was not as secure as it would seem, considering his position of music director: Giovanni Bononcini, an Italian composer, was a rival, maybe even more famous these first years. The following years saw the ascendancy of Handel at Bononcini’s expense. For the fourth season Handel wrote Ottone, which again featured Senesino in the title role, and also the famous Italian soprano Francesca Cuzzoni as Teofane, Ottone’s future wife. She would sing at the Academy for five more seasons, creating, among others, the role of Cleopatra in Giulio Cesare. (Here’s the aria Vieni, o figlio from Ottone, sung by Lorraine Hunt. Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra is conducted by Nicholas McGegan). The Royal Academy of Music lasted for nine years, through the 1728-29 season, collapsing under the weight of huge salaries paid to the lead singers. It reconstituted itself as New Academy a year later. During those years Handel created 13 operas; Giulio Cesare, being the most famous, but also such masterpieces as Rodelinda and Tamerlano. He also wrote several anthems for the coronation of George II (George I died unexpectedly on June 22nd of 1727), one of which, Zadok the Priest, has been sung at every coronation ceremony since that time. Handel became a British citizen in February of 1727; even before that he was made Composer of Music for His Majesty’s Chapel Royal and taught music to royal princesses. Even though the Academy was no more, things were looking good. Handel was famous, well to do, and only 44.Permalink